No van a estar siempre subiendo… Están muy pasadas las bolsas occidentales:

En lo que llevamos de 2017, el Nasdaq ha terminado 49 veces en máximos históricos, el Dow Jones lo ha hecho en 47 sesiones y 37 son las que contabiliza el S&P 500. Así mismo, el mercado norteamericano se ha convertido, utilizando medidas de valoración como el PER, CAPE o capitalización del S&P contra el GDP, en uno de los más caros a nivel mundial.

Fuente: Star Capital Research.

Así mismo, y usando como fuente datos de Valuetree y Bloomberg, el S&P 500 cotiza a primas respecto a sus medias históricas (PER y EV/ebitda) cercanas al 30%.

Un estudio de Deutsche Bank, donde se toma un índice equiponderado de 15 bonos y mercados de acciones de mercados desarrollados, mostraba que ese índice estaba en el nivel más alto de los últimos 200 años. Si bien es verdad que podemos discutir sobre la construcción del mismo (relación entre el mercado desarrollado de 1800 y el de ahora, por ejemplo), lo cierto es que si acotamos plazos, nos encontramos con la misma sobrevaloración.

Hasta un 83% de los propios directivos (CFO), según un estudio de Deloitte, pensaba que el mercado estaba totalmente disparado y que las valoraciones están fuera de precio. Este porcentaje es el más alto en los ocho años que lleva en marcha ese cuestionario.

Preguntados los consumidores americanos por la probabilidad de tener mayores alzas en el futuro, un 65% muestra como estas seguirán produciéndose y que hay que estar comprando. Es decir, el optimismo domina al inversor y este es ajeno a lo que está pagando por cada activo.

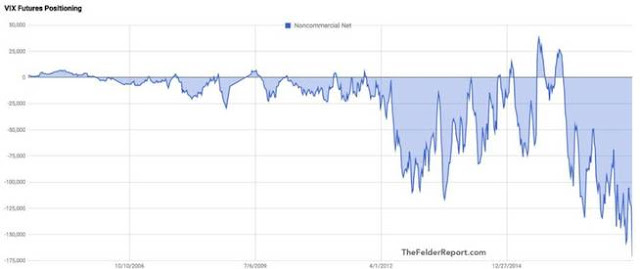

Lo que se muestra en el nuevo récord de posiciones especulativas sobre el VIX. Nunca antes tantos pensaron que el mercado se iba a mover tan poco. Posiciones cortas significa que se apuesta por mercados (S&P) aún más tranquilos que lleven la volatilidad a nuevos mínimos.

Podríamos seguir enumerando decenas de ratios, gráficos y magnitudes varias que tendrían similar comportamiento y que, al final, no dejarían de mostrar que el actual momento de los mercados es, cuando menos, muy interesante y de final incierto.

Mientras sabemos que las valoraciones son altas, que los estímulos de los bancos centrales se van a retirar, que los propios dirigentes de las compañías ven el mercado caro, y mientras magnitudes como la deuda medida por el 'margin debt' alcanzan iguales zonas de máximos históricos, las cotizaciones permanecen ajenas a esos datos económicos e, incluso, a los geopolíticos.

Imagino que, pese a un muy desigual reparto, el nuevo récord en el volumen total de riqueza de las familias norteamericanas les hace entrar en esa fase de confianza absoluta y certeza de que el futuro será aún mejor.

Así las cosas, esto se parece cada vez más a esa estabilidad desestabilizante de la que hablaba Minsky. La complacencia general lleva a pensar que los buenos tiempos están aquí para siempre, y fruto de esa idea se toman mayores riesgos. No hay factores externos que nos preocupen o afecten al mercado, y eso lleva a tomar nuevas posiciones que alimentan la cadena. Hasta el anuncio de la Fed sobre el inicio de la reducción del balance se ha tomado de forma positiva por el mercado... Pero es el propio sistema, por su dinámica interna, el que lleva a la inestabilidad sin necesidad de 'shocks' inesperados. Eso termina por producir los efectos vistos en la crisis financiera donde, sin la existencia de un 'boom' repentino, el sistema colapsó y generó una de las mayores crisis de los últimos tiempos.

Abrazos,

PD1: Interesante. Y si no solo se ha hecho techo y se empieza un mercado bajista…

The Coming Bear Market?

The US stock market today looks a lot like it did at the peak before all 13 previous price collapses. That doesn't mean that a bear market is imminent, but it does amount to a stark warning against complacency.

The US stock market today is characterized by a seemingly unusual combination of very high valuations, following a period of strong earnings growth, and very low volatility. What do these ostensibly conflicting messages imply about the likelihood that the United States is headed toward a bear market?

To answer that question, we must look to past bear markets. And that requires us to define precisely what a bear market entails. The media nowadays delineate a “classic” or “traditional” bear market as a 20% decline in stock prices.

That definition does not appear in any media outlet before the 1990s, and there has been no indication of who established it. It may be rooted in the experience of October 19, 1987, when the stock market dropped by just over 20% in a single day. Attempts to tie the term to the “Black Monday” story may have resulted in the 20% definition, which journalists and editors probably simply copied from one another.

In any case, that 20% figure is now widely accepted as an indicator of a bear market. Where there seems to be less overt consensus is on the time period for that decline. Indeed, those past newspaper reports often didn’t mention any time period at all in their definitions of a bear market. Journalists writing on the subject apparently did not think it necessary to be precise.

In assessing America’s past experience with bear markets, I used that traditional 20% figure, and added my own timing rubric. The peak before a bear market, per my definition, was the most recent 12-month high, and there should be some month in the subsequent year that is 20% lower. Whenever there was a contiguous sequence of peak months, I took the last one.

Referring to my compilation of monthly S&P Composite and related data, I found that there have been just 13 bear markets in the US since 1871. The peak months before the bear markets occurred in 1892, 1895, 1902, 1906, 1916, 1929, 1934, 1937, 1946, 1961, 1987, 2000, and 2007. A couple of notorious stock-market collapses – in 1968-70 and in 1973-74 – are not on the list, because they were more protracted and gradual.

Once the past bear markets were identified, it was time to assess stock valuations prior to them, using an indicator that my Harvard colleague John Y. Campbell and I developed in 1988 to predict long-term stock-market returns. The cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings (CAPE) ratio is found by dividing the real (inflation-adjusted) stock index by the average of ten years of earnings, with higher-than-average ratios implying lower-than-average returns. Our research showed that the CAPE ratio is somewhat effective at predicting real returns over a ten-year period, though we did not report how well that ratio predicts bear markets.

This month, the CAPE ratio in the US is just above 30. That is a high ratio. Indeed, between 1881 and today, the average CAPE ratio has stood at just 16.8. Moreover, it has exceeded 30 only twice during that period: in 1929 and in 1997-2002.

But that does not mean that high CAPE ratios aren’t associated with bear markets. On the contrary, in the peak months before past bear markets, the average CAPE ratio was higher than average, at 22.1, suggesting that the CAPE does tend to rise before a bear market.

Moreover, the three times when there was a bear market with a below-average CAPE ratio were after 1916 (during World War I), 1934 (during the Great Depression), and 1946 (during the post-World War II recession). A high CAPE ratio thus implies potential vulnerability to a bear market, though it is by no means a perfect predictor.

To be sure, there does seem to be some promising news. According to my data, real S&P Composite stock earnings have grown 1.8% per year, on average, since 1881. From the second quarter of 2016 to the second quarter of 2017, by contrast, real earnings growth was 13.2%, well above the historical annual rate.

But this high growth does not reduce the likelihood of a bear market. In fact, peak months before past bear markets also tended to show high real earnings growth: 13.3% per year, on average, for all 13 episodes. Moreover, at the market peak just before the biggest ever stock-market drop, in 1929-32, 12-month real earnings growth stood at 18.3%.

Another piece of ostensibly good news is that average stock-price volatility – measured by finding the standard deviation of monthly percentage changes in real stock prices for the preceding year – is an extremely low 1.2%. Between 1872 and 2017, volatility was nearly three times as high, at 3.5%.

Yet, again, this does not mean that a bear market isn’t approaching. In fact, stock-price volatility was lower than average in the year leading up to the peak month preceding the 13 previous US bear markets, though today’s level is lower than the 3.1% average for those periods. At the peak month for the stock market before the 1929 crash, volatility was only 2.8%.

In short, the US stock market today looks a lot like it did at the peaks before most of the country’s 13 previous bear markets. This is not to say that a bear market is guaranteed: such episodes are difficult to anticipate, and the next one may still be a long way off. And even if a bear market does arrive, for anyone who does not buy at the market’s peak and sell at the trough, losses tend to be less than 20%.

But my analysis should serve as a warning against complacency. Investors who allow faulty impressions of history to lead them to assume too much stock-market risk today may be inviting considerable losses.

PD2: Si caigo, me levanto. No le tengo miedo a caer. Me confieso, tras arrepentirme, y vuelta a empezar… ¡Ánimo!