No entendemos nada de lo que está pasando por ahí… Usamos medios antiguos, del siglo pasado, para acometer errores. La economía es la suma de las actividades y algo más… Despreciamos la nueva economía y sus efectos en el conjunto…

You Cannot Manage New Economies With Obsolete Measuring Tools

First-year students of statistics are routinely warned that, “On average, every person has one ovary and one testicle.” More seriously, they may be told the story of the six-foot man who drowned in a river with an average depth of four feet.

These quips are supposed to prevent students from mindlessly using irrelevant or misleading statistical averages or aggregates. Yet economists often do just that when they measure a country’s or a region’s activity and growth rate by using statistics that bundle together sectors or jobs that, in reality, are behave quite differently from each other.

Often, a single macroeconomic statistic aggregates or averages components that could signal either economic weakness or an acceleration with the potential to rekindle inflation. The resulting uncertainty probably is why, today, the major central banks still hesitate between more monetary easing and its opposite, a return of higher interest rates.

Math, Myths, and Misunderstandings about China

We see one of the most obvious current examples of how misleading averages and aggregates can be in the ongoing, so-called “rebalancing” of the Chinese economy.

Several years ago Andy Rothman, one of the most astute and least “bipolar” analysts of the Chinese economy, acknowledged an emerging consensus that the country’s GDP would soon slow down from its breakneck pace of more than 10-percent growth per annum. He warned, however, that this slowdown would not happen evenly across the board.

Once the huge pent-up demand for infrastructure, plant construction, and housing was satisfied, these sectors would settle into the lower growth rates typical of more-developed economies. However, household spending was still in its infancy, and would probably continue to grow at double-digit rates. It thus would remain “the world’s best consumption story”; but since it could not physically be expected to accelerate beyond the annual 11 percent of recent years, China’s GDP would naturally settle into a much slower growth trend. That, however, would not necessarily be cause for alarm.

Rothman recently updated his views, from which I paraphrase some snippets with my own emphasis added1:

+ Exports haven’t contributed to GDP growth for the past seven years. Only about 10 percent of the goods rolling out of Chinese factories are exported. China largely consumes what it produces.

+ Manufacturing is sluggish, especially in heavy industries such as steel and cement, as China has passed its peak in the growth rate of construction of infrastructure and new homes. But factory wages are up 5 to 6 percent this year, reflecting a fairly tight labor market, and more than 10 million new homes will be sold in 2015. Manufacturing has not collapsed.

+ China has rebalanced away from a dependence on exports, heavy industry, and investment: Consumption accounted for 58 percent of GDP growth during the first three quarters of this year. Shrugging off the mid-June fall in the stock market, real (inflation-adjusted) retail sales actually accelerated to 11 percent in October and November, the fastest pace since March. China has remained the world’s best consumption story.

+ Unprecedented income growth is the most important factor supporting consumption. In the first three quarters of this year, real per-capita disposable income rose more than 7 percent, while over the past decade, real urban income rose 137 percent and real rural income rose 139 percent.

+ The strong consumer story can mitigate the impact of the slowdown in manufacturing and investment, but it can’t drive growth back to an overall 8-percent pace.

So we are far from the gloomy forecasts of analysts who blindly trust GDP statistics aggregating very disparate sectors or, worse, who mistake stock-market fluctuations for evidence of economic strength or weakness.

Measurement Lags Reality

I am not a fervent disciple of the “This Time Is Different” School of Economics. In fact, I have often argued the opposite – that, over its cycles, history tends to “rhyme”2. Still, economies do change over time, and one of the problems of economic analysis is that the way in which we measure activity or growth often lags well behind changes in the real world.

In the late-1980s, for example, Tocqueville Asset Management argued that America’s manufacturing was not dying, as the consensus then proclaimed, but was in fact being reborn, as became apparent in the 1990s. One of our main arguments, articulated with the help of Harvard Professor Robert S. Kaplan, was that corporations were still using accounting methods invented in the 19th century, when basic, heavy industries dominated economic activity3.

In these “ancient” times, raw materials and direct (or “touch”) labor constituted up to 80 percent of total manufacturing costs. It was thus acceptable, when analyzing companies’ sources of profits, to allocate “indirect” costs (those difficult to impute to specific activities or products) in proportion to the easier-to-measure costs of materials or direct labor. But by the 1980s, electronics and other newer and lighter industries used fewer raw materials; their direct labor rarely exceeded 5 to10 percent of total costs. As a result, a situation had developed where a majority of total costs was allocated arbitrarily based on the small portion that was easily measurable.

This obsolete accounting method grossly misestimated which corporate segments were profitable or not, so that corporate strategies often continued to fund less-profitable, traditional activities instead of investing in potentially more-profitable opportunities. This had been detrimental, not only to the competitiveness of individual companies, but also to the overall U.S. economy. Fortunately, by the late 1980s, a more accurate approach to cost accounting was being adopted, which augured well for a US economic revival.

Could History Be About To Rhyme?

Venture capitalist and author Bill Davidow argues that today our techniques for measuring economic performance are obsolete, and thus lead us to reach improper conclusions about the state of the economy. Many economists, policy-makers, and politicians, he says, are still using 20th-century methods to analyze our 21st-century economy, in which two worlds co-exist:

“The physical economy is anemic, struggling, biased toward inflation, and shrinking in many developed countries…. We use dollars to measure most of the activity. If more dollars are spent or earned, we conclude that the economy is growing.

“The virtual economy is robust, biased toward deflation, and growing at staggering rates, everywhere. A lot of the services provided to us in the virtual economy are free. If we paid dollars for those services, they would be counted as part of the GDP and would add to economic growth. But we don’t, so they are not counted.”4

In his analysis, all the “free” services we get on the Internet are actually paid for, not with money that can be counted, but with our privacy and attention. Services like searches on Google, the listing of residential rentals on Airbnb, free email, information storage on Dropbox, phone calls on Skype, hotel and restaurant reviews on TripAdvisor or Yelp, free text messages on WhatsApp, or free music cost zero in money terms, so they are not counted in the GDP. But in fact, they are worth billions.

If advertisers paid us directly to invade our privacy and capture our attention, and we then turned around and spent the money to purchase the services mentioned above, the government would count what they pay us as part of our income and the sale of their services as part of the GDP. There are no accurate numbers, but a partial idea of the value of those services could be derived from the money advertisers spend on digital ads – a projected $114 billion in 2014.

Davidow is not the only one to warn that we are increasingly trying to steer our economies with faulty compasses. British economist Diane Coyle similarly argues that the universally used GDP is no longer a good enough measure of economic performance:

“It is a measure designed for the 20th-century economy of physical mass production, not for the modern economy of rapid innovation and intangible, increasingly digital services.”5

A recent report from Morgan Stanley also reminds us that many of the tools that are supposed to tell economists when growth is about to roll over or accelerate were developed when the economy looked a lot different than it does today:

“Fifty years ago, the US and global economy was largely driven by manufacturing and industrial activity. Today, we are much more of a services- and consumer-driven economy, not just in the US, but all over the world. To be specific, the developed world is 70 percent consumption and services-oriented…. Many of the established economic tools don’t capture this part of the economy properly and over-discount the signals coming from the old economy.”6

Finally, as predicted by Schumpeter’s “creative destruction” concept, the virtual economy not only adds yet-uncounted growth to the real economy, but it also destroys many counted components of the old economy. Edward Jung, former chief architect at Microsoft and now chief technology officer at Intellectual Ventures, explains:

“While GDP measures the market value of all goods and services produced within a country, many stars of the digital age (think Wikipedia, Facebook, Twitter, Mozilla, Netscape, and so on) produce no goods and provide free services. These same star players also tend to undercut the productivity of traditional businesses. Free navigation apps have shrunk sales for Garmin, the GPS pioneer that was once one of the fastest-growing companies in the United States. Skype is killing the international phone call ‘one minute at a time.’”7

So, between uncounted growth from the new economy and creative destruction of parts of the old economy, our traditional macro indicators have the potential to be more confusing than they have been in a long time.

The Sharing, Gig, and Circular Economies

Three models essentially characterize the new economy that I am discussing here: the sharing, gig, and circular.

The sharing model comprises companies such as Getaround, Airbnb, CameraLends, and Loanables, which allow individuals to rent out their cars, homes, or tools when they are not fully utilized.

Dan Neil, in The Future of Everything, explains that, “The utilization rate of automobiles in the U.S. is about 5 percent. For the remaining 95 percent of the time (23 hours), our cars just sit there, a slow, awful cash burn, like condos at the beach.”8

And Davidow quantifies the economic impact of sharing:

“The annual cost of a Honda Civic used for, say, 7,500 miles per year, is around $6,500 per year, or 85 cents per mile. Using a Zipcar for 500 hours a year, approximately the same amount of driving, would cost only $4,250, a saving of $2500 – equal to about 4 percent of a middle class family’s income.”4

The sharing model may be in its infancy, as it potentially applies to many of our belongings. Airbnb CEO Brian Chesky told The New York Times in a 2013 column, “There are 80 million power drills in America that are used an average of 13 minutes. Does everyone really need their own drill?”

In a slightly different vein, BlaBlaCar connects drivers and passengers willing to travel together between cities and share the cost of the journey, while Lending Club puts potential borrowers in touch with potential lenders.

The gig model, with sites like TaskRabbit, FlexJobs, or Gig.com, is the Internet morphing of the traditional freelance economy, where people offer and rent out their skills and talent for specific missions, often for a finite period of time.

The sharing and gig economies often overlap. Uber, for example, is positioned at the intersection of the two, since it allows a car owner to share his car while he also is performing a gig by operating like a taxi driver.

The circular model aims to replace companies’ traditional “resource to waste” way of functioning with a circular “resource to resource” dynamic. Historical industrial processes and the lifestyles that feed on them deplete finite reserves to create products that end up in landfills or in incinerators, while traditional recycling is energy-intensive and generally degrades materials, leading to continuing high demand for virgin materials.

The circular economy aims to design out waste through repair, reuse, and remanufacture. BMW, for example, remanufactures parts to the same quality specifications as new BMW parts, with the same 24-month warranty, at a 50-percent cost saving for customers compared to new parts.9

In the lifestyle area, eBay, Swap.com, thredUP, and Refashioner, which allow people to recycle their clothes, accessories, or almost anything, are good examples of the circular model.

The New Economy Is All Around Us, but…

There is no doubt that the new economy exemplified by the sharing, gig, and circular models has the potential to release much capacity that until now was frozen in idle investments. Conceptually, therefore, this “new economy” should reduce new-car purchases, new hotel-room construction, and other types of investments, while boosting the productivity of existing assets. However, I discussed the matter with a friend who is both active in the hospitality business and an early investor in Uber. He was adamant that I not underestimate the number of mini-entrepreneurs who purchase new cars just to become full-time Uber drivers, or the number of residential or vacation units that are being purchased to be rented full-time.

Moreover, since the income earned by many sharers and gig workers really supplements their regular incomes, many of them do not realize that their gigs or rental incomes qualify as separate jobs. While the additional income from these activities is usually reported to the IRS, the activity may not be correctly captured by various employment surveys.

Just as importantly, the effects of the virtual economy do not fall evenly across the economic spectrum. The lower your income, the more likely it is that you are paying a greater portion of your salary for essentials such as food and healthcare. In that case, you live principally in the physical economy, where the cost of these items has been rising. This segment of the population may be able to get some gig jobs to supplement their incomes, but it generally does not have the money to invest in an Uber car or an Airbnb unit.

This may explain why many people who do not participate in the new economy have the feeling that we still have not fully recovered from the Great Recession, while others actually feel fairly comfortable. Declining prices and additional incomes accrue to participants in the virtual economy, whose members generally are already better off. Two economies, two perceptions of economic reality, but a common GDP.

The truth is that, despite massive research in the last few years, it is hard to gauge the current size and impact of the sharing, gig, and circular economic phenomena on GDP, employment, and even incomes.

But this should not stop us from trying. As Einstein reportedly said, “If we knew what we are talking about, it would not be called research.”

Volatility, Schizophrenia, and Bad Breadth

To my mind, attempting to steer an economy on the basis of aggregates or averages that merge individual sectors with very disparate strengths amounts to trying to tune a carburetor while wearing boxing gloves. The result is likely to be too much stimulus for the strong sectors and starvation for the weak ones. And attempts to try to correct these excesses are likely to worsen the volatility of both economies and financial markets.

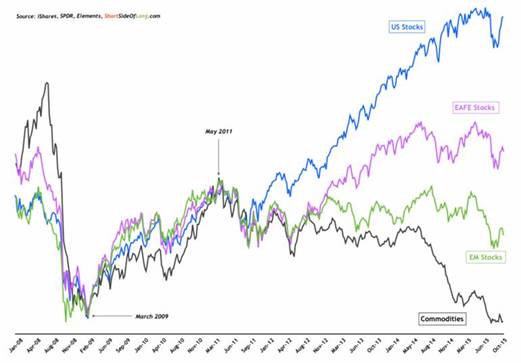

The stage for this type of volatility was set in the last three years, as very large gaps opened between the performances of various regional or sectoral financial markets.

Within the US stock market, similar gaps have developed. The four so-called “FANG” stocks (Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, and Google) and the “Nifty Nine”, which also includes Priceline, eBay, Starbucks, Microsoft and Salesforce, rose strongly in 2015, while the majority of other stocks were down (energy, materials and manufacturing) or broadly unchanged for the year.

Source: StockCharts.com

The kind of financial divergences that have opened in the last three years are usually closed, eventually, and the volatility promised by the lack of economic visibility could portend a challenging coming year for the financial markets.

Abrazos,

PD1: La Fortaleza del hombre: Lo primero que hay que pedir al hombre es que sea, de verdad, hombre, y cabeza de familia: fortaleza, equilibrio, autoridad… Ser cabeza de familia no es mandar, sino ser el que más sufre, el que más se entrega, el que más responsabilidades asume, el que más equilibrio pone en la casa, el que serena las cosas, el que pone el cariño y la corrección necesaria, el que lanza a los hijos a la vida… Ser un hombre de verdad hoy no es sólo saber poner el lavavajillas. Es verdad que el hombre debe colaborar en casa, pero su principal misión ha de ser el fuerte de la casa, no una réplica de la madre…