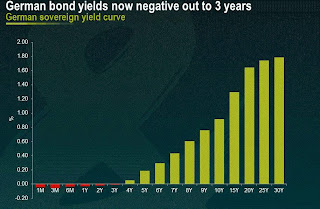

Todavía hay gente que dice que la bolsa sube porque la economía mejora… Esto no es cierto. La bolsa sube porque la gente no sabe dónde invertir sus ahorros. No los meten en pisos, falta caída, no los meten en activos de menos de 2 años, están dando rentabilidades negativas, y optan por comprar bonos que dan muy poco o cerrar los ojos, hacer tripas corazón y comprar bolsa… Ay, con lo alta que están todas las occidentales…

Ayer Dragui actuó: bajo los tipos a cero y a negativo, puso en marcha compra de bonos privados y cédulas… Lo que sea, que el BCE va a comprar unos trilloncitos del ala…, sin poner un duro. Es decir, los compra imprimiendo primero esos trillones que necesita para comprarlos… Demencial!!! Mientras, la bolsa arriba…, hasta que pete…

Interesante esta reflexión:

Bueno, ya está. Tipos de interés reales negativos en muchos países europeos, barra libre de dinero, compra de papeles, y si hace falta más cosas.

Lo de bajar los tipos ni lo comentamos porque ya me dirán en qué va a influir de cara a mejorar la renta o a crear empleo pasar de un tipo de interés del 0,25% a otro del 0,05%. Porque ese es el problema: el creciente desempleo estructural y las rentas en descenso. Y, por consiguiente, en qué va a mejorar la recaudación fiscal y de la seguridad social, y de ahí el modelo de protección social y las pensiones el bajar veinte centésimas los tipos.

Lo otro, la barra libre, pienso que, nuevamente, nos hallamos ante un aguantar como sea hasta Noviembre; dando dinerito fresco para … ¿para qué usarán los bancos ese dinerito fresco que van a recibir?.

Y lo demás, la compra de más de medio billón de papeles varios, la versión europea de las anfetas USA, pero con dos salvedades: ni estamos en el 2011, ni Europa es USA, porque el euro es el dólar. Gasolina para que no se apague el fuego.

Pienso que todas estas medidas adoptadas por el BCE no son más de la versión 2.0 de los Planes E del 2009; con otra salvedad: la situación hoy es completamente diferente a la del 2009: es más dura, más retorcida, todo es más viejo y todo está más deteriorado. Entonces fue un parche para dilatar la situación, ahora es un estímulo para ganar unas semanas.

En otras palabras, el problema es estructural, de modelo, y no se arregla bajando una décima los tipos de interés.

Por ahí fuera hay gente que no ve con buenos ojos ese afán por imprimir, ese afán por salvar a los bancos de sus graves errores de apalancamiento:

ECB President Mario Draghi has cut interest rates again.

Yes, they were already negative. Now they're even more negative. Because in the world of Central Banking if something doesn't work at first the best thing to do is do more of it. Whatever you do, DO NOT question your thinking or your economic models at all.

We've seen this same scheme play out in the US with QE. By the Fed's own admission, its QE programs have only lowered unemployment by 0.13% (mind you, the Fed found this by using the overinflated unemployment data from the BLS, the reality is likely even worse).

Then there's Japan, which has been launching QE for well over 20 years and has never experienced a sustainable uptick in GDP growth or employment. Their thinking was that if spending over 20% of your GDP on QE fails to generated growth, why not announce ANOTHER QE program equal to another 20% of GDP!

At the end of the day, the world is simply too saturated with debt. The reason for this is that Central Banks have promoted easy credit and low interest rates for decades, resulting in everyone and their mother borrowing money to spend, build factories, invest in technology, etc.

This has a diminishing marginal utility. In the 1960s every new $1 in debt bought nearly $1 in GDP growth. In the 70s it began to fall as the debt climbed. By the time we hit the '80s and '90s, each new $1 in debt bought only $0.30-$0.50 in GDP growth. And today, each new $1 in debt buys only $0.10 in GDP growth at best.

Globally today, debt is now a massive overhang and a drag on growth. When you're in debt up to your eyeballs, borrowing more money at cheaper rates doesn't do much for you.

Consider European banks. Taken as a whole, they are leveraged at 26 to 1. In simple terms, this means they have just €1 in capital for every €26 in assets. Remember, for a bank, a loan is considered an "asset." So this means that the bank generally speaking has made €26 in loans for every €1 in capital on its balance sheet.

When you are leveraged at these levels you only need your assets to fall 4% before you've wiped out all of your underlying capital (€26 * 0.04 = €1.04). At that point you are total insolvent.

There is nothing you can do to remedy this situation other than:

1) raise capital

2) pay off your debts

3) default

Borrowing more money at cheaper rates might provide short-term liquidity, but it does nothing to reduce your leverage in the real world. This is why Mario Draghi's efforts to lower interest rates even further into negative territory will fail. It's why generally speaking, all Central bank policy is failing to generate growth: Central Banks can't really do anything to remedy the situation!

However, until the world finally realizes this, we'll continue to see Central banks engage in absurd schemes to try and generate growth. They will ultimately fail. The question is when.

Estamos viendo unos tiempos muy raros, donde los depósitos y los bonos rentan muy poco, para incordio de los rentistas que obtienen muy poco rendimiento de sus inversiones. Interesante lo que cuentan aquí:

The manufacturing outlook for the U.S. doesn't get much better than it is now. In the past 35 years, the ISM manufacturing index has only exceeded its most recent level (59) about 5% of the time. We're in one of those relatively rare periods when the outlook for manufacturing appears to be robust. So why is the Fed still treating the economy as if it were in intensive care? That's a question that must be disturbing the sleep of at least a few FOMC members these days.

As the graph above shows, the ISM manufacturing index has a strong tendency to track the health of the overall economy. The August reading (which exceeded expectations, 59 vs. 57) suggests it is very likely that GDP growth in the current quarter will be at least 3-4%. That would be a distinct and welcome improvement relative to the average quarterly annualized growth rate of 2.2% that we have seen since the current recovery started just over five years ago. On the margin, economic conditions appear to be improving, and that should be showing up in higher bond yields. Yet Treasury yields remain depressed. That can hardly be the result of the Fed's QE purchases, which because of the "taper" of QE3 that started early this year, are now relatively small and scheduled to go to zero within the next month or two. It's not a lack of growth that is keeping yields low, I think it's a lack of confidence.

The employment index of the ISM report was strong too, suggesting that firms are increasingly confident in the future and are planning to staff up accordingly. As the second graph above shows, consumer confidence is also on the rise. Things could be and have been a lot better, but on the margin things are getting better, and that is what's most important from the market's perspective.

One thing stands out like a sore thumb, however: this year's growing gap between manufacturing conditions in the U.S. and the Eurozone. The Eurozone is really struggling, while the U.S. is doing noticeably better. Eurozone weakness, lingering fears of a Japanese-style stag-deflation, and mounting geopolitical risks in Ukraine and the Middle East are likely all factors keeping U.S. yields depressed. Confidence may be on the rise, but it is still relatively low and there are still plenty of reasons for the market to be nervous about the future.

Not surprisingly, there has been a huge relative underperformance of Eurozone equities in recent years. Since August of 2010, the S&P 500 has beaten the Euro Stoxx index by over 60%. Over the same period, the Nikkei 225 has beaten the Euro Stoxx index by over 40%. If the long-struggling Japanese economy is now beating the Eurozone economy, why are 10-yr Japanese bond yields a mere 0.5%? Even though the Nikkei is doing pretty well, it is still quite low from an historical perspective and the yen is weakening (today falling to 105, down from a high two years ago of 78). Although a weaker yen appears to be good for stocks, as I argued last year, it does not inspire a lot of confidence per se.

Treasury yields have been falling since 1980, resulting in the greatest bond bull market of the century. Falling inflation was the main driver of falling yields, but that ceased to be the case about five years ago. I think the decline in yields in recent years owes more to a flight to quality and safety than it does to deflation. The market is still willing to pay a substantial premium for things, like Treasuries, TIPS, and gold, that offer protection from risk.

The above graph suggests that the reason yields are unusually low today is that the bond market and the Fed are very worried about the risk of a slowdown in U.S. economic growth. The market figures that U.S. growth is capped on the upside at 2% a year due to a combination of demographics (the aging of the baby boomers) and weak productivity, which in turn is the predictable result of today's weak business investment climate. U.S. growth could easily be derailed, the thinking goes. The chart above suggests that 5-yr TIPS are priced to the assumption that U.S. economic growth averages 0-1% over the next few years. The market is willing to pay a significant premium for TIPS in exchange for their inflation hedging properties and their guaranteed, risk-free real yield.

The graph above compares the inverse of 5-yr TIPS real yields to the earnings yield on the S&P 500. The correlation over time looks reasonably good. When real yields were high in the late 1990s, earnings yields on stocks were very low, because the market was very confident that economic growth and profits would remain strong. (That turned out to be wrong, of course.) Today, with real yields in negative territory and earnings yields relatively strong, the market is worrying that economic growth will be weak and profits will fall. No one is willing to pay much of a premium to own stocks these days, whereas they are willing to pay a significant premium to enjoy the safety of TIPS.

The graph above compares the inverse of the real yield on 5-yr TIPS (a proxy for their price) to the price of gold. TIPS and gold prices have tracked each other amazingly well for the past 7-8 years. Why? Because they are both assets that have intrinsic hedging and risk-reducing properties. Demand for the safety and inflation protection of TIPS has been strong, and demand for the inflation protection and end-of-the-world-as-we-know-it protection of gold has also been strong. Demand for both has weakened in the past 18 months. Why? Because confidence, which was extremely depressed for years following the Great Recession, is slowly reviving.

If the nominal and real yields on Treasuries appear to be unusually low, and the prices of TIPS and gold appear to still be unusually high, it is because the world is still willing to pay a premium for safe assets. That willingness appears to be weakening on the margin, however, and more news like today's ISM manufacturing support will likely serve to further boost confidence and weaken the demand for safe assets going forward. This would likely manifest itself in a significant rise in real and nominal Treasury yields, and a decline in the price of gold. Equity investors needn't worry, however, since yields will only move higher as the economic outlook brightens.

As this last chart shows, gold prices overshot commodity prices beginning in 2009, and appear to have been correcting that overshoot in recent years. In a sense, gold at $1900 was pricing in a colossal inflation mistake on the part of the Fed that has failed to materialize. I won't be surprised if gold declines to $900 or so within a few years. Full disclosure: at the time of this writing I have no position in gold.

Un abrazo,

PD1: Este verano que hemos convivido muchas horas con mis hijos. Lo que más he apreciado es el "buen rollito" que mantenemos. Nos llevamos bien, nos queremos, sabemos convivir, dejamos a cada hijo su intimidad y una dosis de libertad que le permite pasárselo bien y relacionarse con sus amigos… No hago más que dar gracias a Dios por ello, por este hogar que hemos formado de armonía y tranquilidad…

Pero no todo el mundo está en nuestra misma situación. ¡Qué cantidad de familias tienen problemas con los chicos! Hay por ahí mucho chantaje emocional y agresiones verbales que da miedo… Mira lo que dicen aquí.

¿Cómo hemos conseguido tener tanta paz en casa? Muy simple: estando con los hijos, ayudándoles, sin obligarles a que hicieran cosas porque sí, dándoles mucha libertad, sin ser amigotes de ellos, sino sabiendo que somos sus padres y que debemos formarles, sin ser sus colegas, que no lo somos…, y sobre todo, queriéndolos, estando a gusto con ellos y tratando de que ellos estén a gusto en casa, que disfruten de un cálido ambiente familiar. No debemos pretender que sean un calco nuestro, o que hagan lo que a nosotros nos gustaría, o que sean super hombres…, no descarguemos en ellos nuestras frustraciones. Mucha alegría, muchas risas, y sin dramatizar los errores que se cometen…, por su parte, y por la nuestra.