Tras seguir haciendo máximos históricos, unos opinan que sí, que está muy cara y que debe recortar…, aunque llevan muchos meses diciendo lo mismo y no recorta ante la falta de alternativas, ante la dificultad de encontrar rentabilidad en activos alternativos:

Amid a looming war with North Korea, stalled tax reforms and Trump threatening to annul trade agreements, the S&P 500 seems suspiciously unfazed…

It’s well known that stock markets tend to have a positive take. One familiar example is how they behave in a recession. Naturally, when the economy starts contracting rather than growing, stocks go down. But then the market always seems eager to demonstrate its ability to bounce back again. An average of three months before a recession ends, stocks will typically show a sudden upturn. Although macroeconomic figures often still point to an ongoing contraction, the market has already priced this in and bottomed out. This is referred to as ‘climbing the wall of worry’.

It’s worth noting that such optimism is not unique to recessions. Trump wins the election? There will be tax cuts, so it’s great for stocks! Trump threatens to shut down the government if it won’t fund the wall with Mexico? Great bargaining chip: certainly better than starting a trade war! Trump demands trade tariffs? Don’t take him too seriously. He won’t get it through Congress, anyway. So it’s great for stocks! I admit, I may be exaggerating a bit, but in the last six months, I have actually seen this kind of reasoning being used, though not always by the same people.

Mind you, I’m not saying the US markets just ignore the news. There were two days in August in which the S&P lost around 1.5% due to the mounting tensions surrounding North Korea. In both cases, however, it quickly bounced back: bargain hunters entered the market, rapidly bringing it back to its previous level. In spite of Donald (a.k.a. ‘I-want-tariffs’) Trump’s statements and North Korea’s antics, this week the S&P 500 closed at a new all-time high.

US stocks are expensive!

On the face of it, there’s of course nothing wrong with this. Ultimately, a company’s growth and profit outlook are what really matter when it comes to valuation and as long as there are just ominous headlines and no concrete measures or real consequences, what’s not to like? The global economy will keep humming along and inflation – typically considered a troublemaker – won’t be a concern. So why should stock prices fall?

Erm, well, because they’ve gotten too high? Let’s not forget that the markets have behaved optimistically for much longer than just the last six months – they’ve been like that for over eight years. Whereas they initially seemed only to be compensating for excessive pessimism (the markets can overreact in both directions), in recent years, US stock prices have consistently risen more quickly than underlying earnings. So the markets are consistently pricing in higher earnings. That’s not to say they won’t eventually materialize, but the gap between stock prices and earnings is starting to look more like a gaping hole.

The measure most commonly used to show that stocks are overvalued is Robert Shiller’s price/earnings ratio, also known as the Cyclical Adjust Price Earnings (CAPE) measure, or simply ‘Shiller PE’. Unlike the usual price/earnings ratios, the Shiller PE doesn’t look at expected profits or the last year’s profits, but the average over the last ten years in real terms. The reason why Shiller uses such a long timescale is to smooth out the volatile nature of earnings and create a more stable picture. The graph above, which shows changes in the Shiller PE over time, leaves little to the imagination. There are clear outliers indicating the major stock market bubbles of 1929 and 2000, and the damage they left in their wake. In fact, the level of the Shiller PE is now suspiciously close to where it was during the 1929 crash, which back then marked the start of the Great Depression. According to this measure, the only time prices were higher was during the 2000 Internet bubble… which is indeed worrying.

Rose-colored glasses

Leave it to the stock market pundits, with their unrelenting optimism, to put a positive spin on this, too. Certainly, 30x seems high and looks intimidating, but in this case, there is an automatic improvement in the pipeline. As mentioned, the Shiller PE looks at the real earnings of the last ten years, thereby supporting the positive spin: it was ten years ago that the crisis struck and US earnings took an unprecedented hit. Based on the Shiller figures, real earnings dropped a staggering 92% between June 2007 and March 2009. On a graph it looks like this:

Over the next two years, that decline in earnings will fall out of the equation

The extremely low earnings figures are currently all still being included in the Shiller PE, but will gradually fall out of scope over the next few years. In other words, even if earnings do not grow appreciably in real terms during that time (which seems a bit pessimistic), the Shiller PE will decline ‘naturally’. The graph below shows the level of the Shiller PE until 2021, if earnings remain constant: Shiller PE: 30 or 25?

Source: Robeco, Shiller

In short, whereas pessimists view a Shiller PE of 30x as a sign of impending disaster, optimists (=the stock market) would probably use a different price/earnings ratio. Though it’s not the true Shiller PE, this adjusted Shiller PE (which actually looks at earnings over the last six years, rather than ten) stands at a ‘mere’ 25x. Even in historical terms, that’s still high, but likely not alarming enough to stop stock prices from rising.

Incidentally, each year Robeco publishes a five-year outlook on the financial markets, which looks at more than just the Shiller PE. The graph below was taken from that publication. Other valuation measures also suggest that the US market is currently overvalued.

Other measures also suggest that the US market is overvalued.

Source: Robeco Expected Returns 2018-2022

Y otros no lo ven tan mal y piensan que seguirá subiendo…:

The global economy and global financial markets are huge, but just how huge? Answer: a lot bigger than most people realize. Here are some charts which help put things in perspective. They also show that what's going on today is not unprecedented nor extraordinary. As always, all the charts contain the most recent data available at the time of this post.

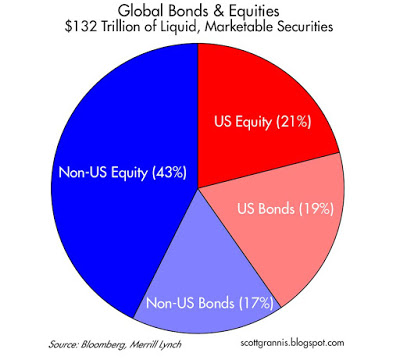

Global GDP is roughly $80 trillion, about four times the size of the US economy. As the chart above shows, the global economy supports actively traded bonds and stocks worth $132 trillion, of which about 40% are US-based. There's nothing unusual about any of this, considering that a typical US household has a net worth (stocks, bonds, savings accounts and real estate) equal to about three times its annual income.

As the charts above show, the market cap of Non-US equities has grown at a much faster rate than US equities since 2004 (US equities have grown at a 5.4% annualized rate, non-US equities at a 8.9% annualized rate). US equities are now worth about 50% of the value of non-US equities, down from more than 80%. Non-US equities have suffered somewhat, however, due to the dollar's 5% rise (on a trade-weighted basis) over the period of these charts, but that's relatively insignificant in the great scheme of things.

The defining characteristic of the current US economic expansion is its meager 2.1% annualized rate of growth, which stands in sharp contrast, as the chart above shows, to its 3.1% annualized rate of growth trend from 1965 through 2007. If this shortfall in growth is due, as I've argued over the years, to misguided fiscal and monetary policies, then the US economy has significant untapped growth potential and could possibly be $3 trillion larger today if policies were to become more growth-friendly.

As the chart above shows, the value of US equities relative to GDP tends to fluctuate inversely to the level of interest rates. This is not surprising, since the market cap of a stock is theoretically equal to the discounted present value of its future earnings. Thus, higher interest rates should normally result in a reduced market cap relative to GDP, and vice versa. Since 10-yr Treasury yields—a widely respected benchmark for discounting future earnings streams—are currently at near-record lows, it is not surprising that stocks are near record highs relative to GDP. If the economy were $3 trillion larger, however, stocks at today's prices would be in the same range, relative to GDP, as they were in the late 50s and 60s. Valuations are relatively high, to be sure, but not off the charts nor wildly unrealistic.

As the chart above suggest, over long periods the value of US stocks tends to rise by about 6.5% per year (the long-term total return on stocks is a bit more due to annual dividends of 1-2%). The chart also suggests that the current level of stock prices is generally in line with historical trends.

Adjusting for inflation, we see that stock prices tend to rise about 3% a year, and the current level is not unreasonably high, as it was in the late 1990s.

US equities have significantly outpaced Eurozone equities over the past nine years. That has a lot to do with the fact that the US economy has grown faster as well.

US households (i.e., the private sector) have a net worth that is approaching $100 trillion. That figure has been growing at about a 3.5% annualized rate for a very long time. The current level of wealth is very much in line with historical experience.

Adjusting for inflation and population growth, the average person in the US is worth almost $300,000. That is, there are assets in the US economy which support our jobs and living standards (e.g., real estate, equipment, savings accounts, equities, bonds) worth about $300,000 per person. We are richer than ever before, but the gains are very much in line with historical experience. (Note: the last two charts are based on Q1/17 data from the Federal Reserve. Data for Q2/17 will be released Sept. 21st, at which time I will be able to update these charts.)

Así que tú mismo… Un abrazo,

PD1: No comas todo lo que puedes, no gastes todo lo que tienes, no creas todo lo que oigas, no digas todo lo que sabes. - Proverbio chino.