Las tendencias las lees en el blog. Las estrategias, dónde invertir, lo cuento a los amigos.

20 noviembre 2018

los bancos europeos son una bomba de relojeria

19 noviembre 2018

¿Tenemos o no tenemos inflación?

16 noviembre 2018

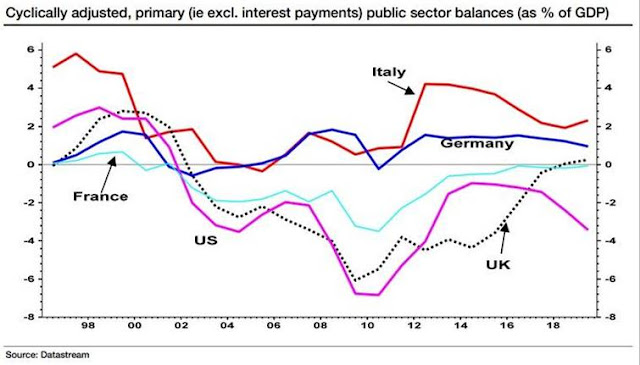

además del Reino Unido, el problema es Italia

15 noviembre 2018

Alemania tiene crecimiento negativo

14 noviembre 2018

cuidado con los PERs baratos

Hay muchos analistas que piensan que esto va a subir ya que las valoraciones son baratas. La expansión este año de los beneficios puede ser pura fantasía, ya que en un entorno de ralentización y de subida de tipos de interés, estas valoraciones pueden quedarse caducas en poco tiempo…

El atractivo de los bancos europeos, pura apariencia, según los inversores

Es cierto que los principales bancos de Europa han superado una prueba importante sobre su capacidad de resistencia en las recientes pruebas al sector, pero los reforzados balances sirven de poco cuando generan una rentabilidad tan escasa comparada con sus competidores estadounidenses, dicen los inversores. Los resultados de los tests de estrés, publicados el viernes por la Autoridad Bancaria Europea, muestran que el sector goza de una razonable salud financiera y concluyen que las 48 entidades analizadas serían capaces de soportar baches económicos como una caída en los precios inmobiliarios o de la deuda. Por primera vez desde 2009, el chequeo del sector en la UE mostró que todos los grandes bancos superaron un umbral de capital clave en el escenario económico más adverso. Sin embargo, el vicepresidente del Banco Central Europeo, Luis de Guindos, dijo el lunes pasado que una docena de bancos que se quedaron por debajo del umbral del 9 por ciento en el escenario adverso deberían reforzar sus posiciones de capital.

Entre estos bancos se encuentran Deutsche Bank, BNP Paribas y Societe Generale.

Los temores a nuevas ampliaciones de capital explican en parte por qué los inversores todavía ven con recelo el sector. El índice STOXX de la banca europea, que ha caído un 20 por ciento en lo que va del año, cotizó sin grandes cambios el lunes después de conocerse los resultados. Parece que esta reticencia continuará ante el clima de debilitamiento de las perspectivas económicas en Europa, según gestores de fondos y analistas.

Una década después de la crisis financiera y a pesar de los años de estímulo monetario, el crecimiento de Europa se está desacelerando, y los economistas encuestados por Reuters pronostican un crecimiento del PIB para todo el año en la zona euro del 2,1 por ciento este año y del 1,8 por ciento el próximo.

Eso se debe a unas perspectivas de mayor debilidad en parte por la crisis política de Italia, la desaceleración en Turquía y las posibles consecuencias del divorcio de Reino Unido de la Unión Europea, factores que fueron incluidos en los escenarios de prueba de estrés.

A nivel superficial, las acciones de los bancos europeos parecen gangas. La valoración del sector a través del índice bancario STOXX apenas se sitúa por encima de mínimos históricos, mucho después de que las entidades se hayan deshecho de los activos tóxicos que echaron por tierra la fe en el sistema financiero en 2007.

Pero el hecho de que los niveles de capital bancario ahora sean aproximadamente tres veces más altos que los niveles anteriores a la crisis no ha logrado alejar la inquietud sobre el origen del crecimiento de los ingresos bancarios.

"La rentabilidad sigue siendo un gran problema para muchos bancos en Europa", dijo a Reuters Mario Quagliariello, director de análisis económico de la EBA.

AÑO COMPLICADO

Los bajos tipos de referencia (del 0,75 por ciento en Reino Unido y del -0,4 por ciento en la zona euro) están obligando a las entidades a recortar márgenes y asumir mayores riesgos a medida que la demanda de préstamos se desacelera en un contexto de estancamiento del crecimiento, dando lugar a unas rentabilidades pobres para los inversores.

"Las acciones de los bancos europeos han tenido un año difícil hasta ahora, y hasta que no haya datos económicos que sugieran un crecimiento económico sólido en la zona euro, es poco probable que las acciones de los bancos se recuperen", dijo Mike Olivia, asesor de WestPac Wealth Partners, que tiene acciones en el sector bancario.

Los directivos bancarios también tienen menos libertad para ganar dinero en la banca de inversión después de la crisis financiera, argumentan los inversores. Este problema se ve agravado por una incapacidad igualmente sorprendente para contener los costes.

Además, el endurecimiento de la regulación ha hecho que el sector sea más seguro pero menos lucrativo, según los gestores de fondos, lo que hace que sea más difícil vender las acciones bancarias a sus clientes de seguros y fondos de pensiones, que demandan mayores recompensas por unas inversiones que perciben como arriesgadas.

La rentabilidad media de los bancos de la UE en 2017 se situó en el 5,6 por ciento, casi la mitad del nivel de 2007, cuando estaba en el 10,6 por ciento, según datos de la Federación Bancaria Europea, y por debajo del 9 por ciento registrado por sus competidores de EEUU.

Los negocios de banca de inversión de las entidades estadounidenses aumentaron su cuota de mercado a expensas de sus rivales europeos, víctimas de una debilidad mayor bursátil y una mayor regulación en Europa, y otorgaron unos márgenes operativos -una medida clave de la rentabilidad- más altos a los bancos de Estados Unidos.

Según los datos de Coalition, los principales negocios de renta variable y de renta fija de los bancos estadounidenses alcanzaron márgenes del 31 por ciento y el 42 por ciento en la primera mitad de este año, en comparación con el 14 por ciento y el 27 por ciento de esos mismos negocios en los bancos de inversión más grandes de Europa.

IMPOTENCIA

Las dos señales de compra más grandes para los inversores en los bancos son un alza en los tipos de interés, seguida del crecimiento en la demanda de deuda. Pero ambos factores están en manos de los responsables de las políticas monetarias, no de los directivos de los bancos, señaló Vincent Vinatier, gestor de carteras de AXA IM, que posee acciones bancarias.

"La mayoría de la gente duda de que volvamos a ver los tipos de ganancias que vimos antes de la crisis (...) El ROE (rendimiento sobre el capital) será solo una fracción de lo que fue", dijo Vinatier a Reuters.

Los anhelados aumentos de tipos llegarán, pero los que volvieron a entrar en acciones de los bancos europeos en febrero, cuando las esperanzas de un cambio en la política monetaria alcanzaron su auge, se vieron castigados con una caída del 20 por ciento en las cotizaciones. Cuando los tipos suban, es probable que ocurra en pequeños incrementos tras señales claras de los dirigentes de las políticas monetarias en la UE.

Y el impacto positivo sobre los márgenes de los bancos probablemente será compensado en gran medida por la necesidad de devolver los préstamos ultrabaratos ofrecidos por el Banco Central Europeo en los últimos años, reemplazándolos con fondos más costosos, según los analistas de Berenberg.

Los mayores costes de la deuda también podrían resultar fatales para una gran cantidad de las llamadas 'firmas zombi', compañías con dificultades para pagar sus deudas con sus beneficios actuales.

COSTES

Ante las dificultades para elevar los ingresos, se considera fundamental controlar los costes en la batalla para recuperar a los inversores.

"Aún queda mucho más por reducir costes, es decir, más cierres de sucursales y reducción de personal", dijo Marc Halperin, directivo del Federated International Leaders Fund, que, entre otros, invierte en ABN AMRO, Grupo AIB , Credit Suisse, BNP Paribas, Intesa Sanpaolo y UniCredit. Los gastos del banco de inversión de Barclays, por ejemplo, continúan disparados, impidiendo que el banco cumpla su objetivo de reducir el ratio de eficiencia, que compara costes con ingresos, por debajo del 60 por ciento.

El director financiero de Standard Chartered, Andy Halford, dijo que su banco "prácticamente no logró avances" en la reducción de costes este año en un correo electrónico filtrado que envió el mes pasado a la plantilla.

Y los beneficios logrados por la reducción de puestos de trabajo y sucursales se han visto eclipsados por nuevos gastos en tecnología y seguridad cibernética.

Los bancos han dejado atrás la época de las grandes multas por malas conductas, pero el cumplimiento de las normativas es un gasto general inevitable que aumentará a medida que se amplíen sus actividades.

Y las promesas de pagos de dividendos anuales del 4, 5 y hasta del 6 por ciento tampoco atraen a los inversores, porque los grupos de energía, de telecomunicaciones y las aseguradoras europeas pueden ofrecer los mismos dividendos con un riesgo reducido, dijeron gestores de fondos.

Según datos de Berenberg, los bancos son el segundo sector más barato en términos de PER (relación de la cotización con las expectativas de beneficio), cotizando a 9,1 veces las estimaciones de consenso sobre los beneficios de 2019, con un descuento del 30 por ciento en los precios de mercado, y ofreciendo un rendimiento estimado de 5,79 por ciento para 2019.

Sólo el sector de automóviles es más barato.

Aunque son neutrales con respecto al sector, los analistas de Bernstein dijeron que los inversores rara vez tuvieron una mejor oportunidad de comprar el ROE que actualmente ofrece el sector a precios tan baratos.

"Si uno quisiera ver el lado positivo, los bancos europeos tienen una valoración algo barata con respecto a su nivel de ROE en comparación con lo que sugiere la historia".

Los inversores más bajistas dicen que el reducido interés por los bancos europeos se debe a los crecientes temores de que el proyecto europeo esté condenado en última instancia, o a que otra crisis financiera global provocada por las guerras comerciales o la insolvencia soberana está a la vuelta de la esquina.

"La próxima crisis financiera será provocada por la deuda soberana, en lugar de por los bancos. Sin embargo, los bancos son dueños de gran parte de la deuda soberana, por lo que existe un riesgo de contagio", dijo Matthew Gallagher, miembro de Odinic Advisors.

"Grecia e Italia están comenzando a mostrar grietas y no recibirán ayuda mientras los tipos de interés aumentan en Estados Unidos".

Abrazos,

PD1: Es curioso al leer el evangelio nos damos cuenta de la poca fe que tenían los apóstoles. El señor se lo echa en cara continuamente. Y eso que estaban con Él, que convivían con Él. Es un cierto alivio para nosotros hoy que, como ellos, debemos pedir que nos aumente la fe cada día…