Al margen del desastre del Brexit, que sigue coleando y en el fondo es un auténtico fiasco se haga como se haga, el problema es Italia que no ha sido capaz de seguir la senda de otras economías…, y es muy grande.

Desde Societe Generale:

Edwards writes that a similar heated debate among economists has exploded over the current battle between the Italian government and the European Commission (EC) about Italy's proposed budget expansion.

The orthodox view is that the Italian government is pursuing a ruinous economic policy and an unfolding crisis of confidence will drive up Italian bond yields, threatening contagion and a repeat of the 2011/12 eurozone crisis. Hence the orthodox view is that the newly elected Italian government must sing to the EC’s fiscally austere song-sheet.

The SocGen strategist counters that many of the reasons for Italy's low growth problems have nothing to do with being in the euro, and instead focuses on educational attainment and Italy's moribund productivity. He explains:

Italy's membership of the eurozone has got nothing to do with its educational attainment, university enrolment, corporate governance, legal delays, or lastly and most crucially, red tape that binds Italian businesses as tight as an Egyptian mummy.

Italy's position of 51 overall in the World Bank rankings should be a national embarrassment (see chart below, and note Italy is equally ranked 1 in ‘trading across borders’ only because it is in the EU)

In this context, Edwards proposes that the straitjacket of the single currency and hence Italy's inability to devalue "have merely brought these chronic competitive issues to the fore. Indeed none of these problems are new. Yet the Italian economy managed to keep pace with other major industrialised nations quite happily though the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s." And, as Edwards shows, it was not until the 2011 eurozone crisis that Italian GDP began to underperform Germany (see chart below).

This leads Edwards to a disturbing conclusion, namely that "the establishment consensus is engaged in wishful thinking if they believe Italy will ever be able to implement sufficient structural reforms to restore competitiveness (and remember that structural reforms are by their nature often deflationary, and need an expansionary fiscal policy to cushion the initial depressing effects on the economy something the EC would never allow)."

Meanwhile with inferior productivity growth, Italy’s relative real exchange rate rises every year as unit labour costs deviate further and further from the rest of the eurozone (see chart below).

In Edwards' view, without radical measures Italy will likely never ever grow inside the eurozone (Italian GDP is barely above where it was when they joined the euro). Instead, the SocGen strategist is convinced that "Italy will leave the eurozone during the next economic crisis as youth unemployment roars upwards from the current 30% towards 50%, increasing even further the majority support of young Italians to leave the EU (poll conducted by Benenson Strategy Group in October 2017 link.)"

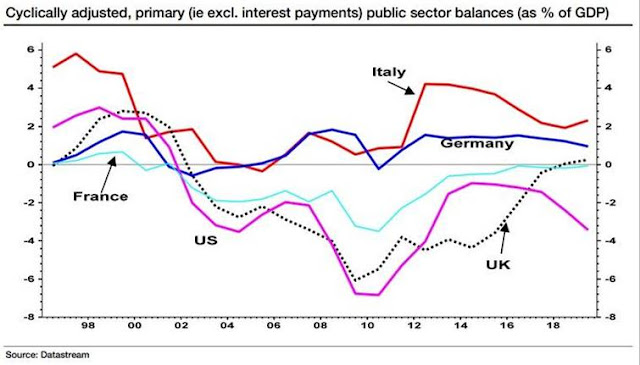

Which goes back full circle to the austerity being imposed upon Italy by the EU: it is this fiscal straitjacket that the Italian government has been forced to wear over the last decade that has become intolerable to the Italian electorate (see chart below showing persistent large primary surpluses) according to Edwards, who notes that "it was only a matter of time before they broke free, but to be honest I am surprised it has taken so long for this confrontation with the EC to occur."

Alberts concludes with some observations on the timing of Europe's inevitable unwind, in which he cites the French finance minister Bruno Le Maire, stating that he fully agrees with the Frenchman's view:

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard of the UK's Daily Telegraph reports that “France has launched a feverish campaign to shore up the euro before the next global downturn, warning that monetary union is not strong enough to withstand another crisis and the euro will face disintegration without fiscal union.

“Bruno Le Maire, the French finance minister, said there are just weeks left for Germany and the Dutch-led "Hanseatic League" to grasp the nettle on long-delayed reforms. “Either we get a eurozone budget or there will eventually be no euro at all,” he said. “If there was a new financial and economic crisis tomorrow, the eurozone could not respond. It is really urgent that we build up the eurozone’s defences. We have been talking for too long,” he told the Handelsblatt newspaper.

“Time is running out before the EU’s make-or-break summit on the future of the euro next month. The global expansion is looking tired and fragile. Mr Le Maire said Europe’s leaders had failed to learn the lessons of 2008 and the 2012 debt crisis. They had not completed the banking union, or broken the ‘bank-sovereign doom loop’ with full help from the bail-out fund (ESM). Nor had they completed the capital markets union, or established a fiscal entity to bind EU economies closer together. “I am not being pessimistic, I am facing reality,” he said.

As noted above, while Edwards "totally agrees" with Bruno Le Maire’s realism, he doesn’t think time is running out, instead "I think time has run out." In keeping with his structural bearishness, Albert claims that "the next global economic downturn is coming and it will throw the eurozone into another major crisis, but one in which Italy will elect politicians committed to leaving the eurozone (actually it might be the same politicians as we have today, but who will feel empowered to show their true anti-euro colours)."

There is one thing Edwards disagrees with: as he says, Bruno Le Maire’s solution of an EU banking union and fiscal transfers to a perpetually stagnant Italy "is not the answer. These reforms are not throwing down a ladder to help Italy climb out of its hole and escape. Instead it will merely be throwing food down the hole to keep a trapped Italy from fiscal death."

Which brings us to Edwards' gloomy denouement: "make no mistake cometh the crisis, cometh the ECB Central Banker" says Edwards who remembers "the fabulous quote" from Vitas Vasiliauskas, governor of Lithuania's central bank who several years ago claimed that central bankers are magic people!

His quote in full back in May 2016 was “Markets say the ECB is done, their box is empty, but we are magic people. Each time we take something and give to the markets - a rabbit out of the hat.”

They are indeed magic people and a few other things besides. Will it be enough? I doubt it.

Assuming Edwards is correct, where does that leave us? Not surprisingly, in a very gloomy place:

Every major economy is close to falling into a deep hole from which they will struggle to emerge. The monetary and fiscal ladders thrust down into the 2008 pits of despair will no longer be as available next time around. It is difficult to identify who will fall furthest, but of one thing I am sure: the populists that will emerge to ‘save us’ will use fiscal and monetary stimulus in a way that can only be dreamed of. You ain’t seen nothing yet!

Y nuestro triste problema es que los guiris, en términos generales, nos identifican con Italia… Abrazos,

PD1: Como dice el Obispo Munilla: hay que empezar todos los días…