¿Cuándo ocurrirá?

El “margin debt” es el término que dicen los yanquis a las operaciones de compra de bolsa a crédito. Muchos quieren ganar más y optan por comprar lo que tienen y piden un préstamo para acumular aún más… En las épocas de tendencia alcista, es un chollo. Pero en los momentos de debilidad, se pierde todavía más.

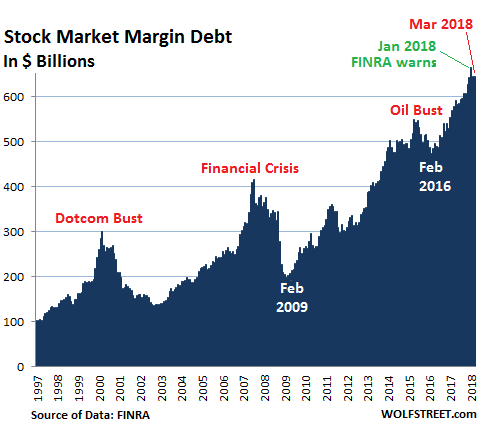

Lo suyo es que en estos meses de techo del mercado, de correcciones de las bolsas, este apalancamiento se hubiera disminuido bastante… Pero esto no ha ocurrido todavía. Debe salir papel al mercado de una fase de desapalancamiento para reducir las pérdidas de tener más comprado, para reducir lo que está a crédito, aunque seguimos esperando…:

An Orderly Unwind Of Stock Market Leverage?

That would be a first, but it might be happening. Everything in slow motion, even market declines?

There is nothing like a good shot of leverage to fire up the stock market. How much leverage is out there is actually a mystery, given that there are various forms of stock-market leverage that are not tracked, including leverage at the institutional level and “securities backed loans” offered by brokers to their clients (here’s an example of how these SBLs can blow up).

But one type of stock-market leverage is measured: “margin debt” – the amount individual and institutional investors borrow from their brokers against their portfolios. Margin debt had surged by $22.9 billion in January to a new record of $665.7 billion, the last gasp of the phenomenal Trump rally that ended January 26. But in February, as the sell-off was rattling some nerves, margin debt dropped by $20.7 billion to $645.1 billion.

By March, those worries have settled down, and margin debt ticked up a bit to $645.2 billion, but remained $20.5 billion below January, according to FINRA, which regulates member brokerage firms and exchange markets, and which has taken over margin-debt reporting from the NYSE.

In January, days before the sell-off began, FINRA warned about the levels of margin debt. It was “concerned,” it said, “that many investors may underestimate the risks of trading on margin and misunderstand the operation of, and reason for, margin calls.” Investors might not understand that their broker can liquidates much or all of their portfolio “under unfavorable market conditions,” when prices are crashing. “These liquidations can create substantial losses for investors,” FINRA warned. And when the bounce comes, these investors, with their portfolios cleaned out, cannot participate in it.

This is why leverage such as margin debt is the great accelerator for stocks on the way up as it creates new liquidity that goes into buying stocks. And this is also why margin debt is the great accelerator on the way down, when forced selling kicks in and liquidity just disappears.

But this is not the scenario the markets are in at the moment. Everything is so orderly, though it’s a lot more volatile than it was during the run-up last year. And margin debt too has declined in an orderly manner:

For the 12-month period through March, margin debt rose $67.6 billion, down by nearly half from the 12-month period ended in January, when margin debt had soared $112.2 billion, the fifth-largest 12-month gain in the history of the data series, behind only the 12-month periods ending in:

December 2013 ($123 billion)

July 2007 ($160 billion)

March 2000 ($133.7 billion)

November 1997 ($132 billion).

Margin debt has soared since 2009, with only a few noticeable down-periods – including during the Oil Bust when the S&P 500 index dropped 19%, and the 2011 sell-off when the S&P 500 index dropped 18%. In March, it exceeded the prior peak of July 2007 ($416 billion) by 55%. But that’s down from 60% in January.

This chart shows the longer view:

During margin debt’s peak-to-peak surge of 60%, nominal GDP (not adjusted for inflation) rose 32% and the Consumer Price Index 20%. Historically, this disconnect has had a tendency to correct via messy panicked crashes and deleveraging. The last three spikes in margin debt are indicated in the chart above. The first two were followed by market crashes. And now?

Clearly, this will correct again. It always does. But the manner in which it corrects may well be very different, more orderly rather than panicky, taking its goodly time, given the glacial pace of the Fed’s tightening and the large amounts of liquidity still in the market looking for a place to go. And this type of gradual unwinding of stock-market leverage would be a first, but it might be happening before our very eyes.

Si enfrentamos el apalancamiento con la evolución de la bolsa, vemos que han ido muy parejos:

Así que si se desapalanca el sistema, tocará salir mucho papel…

Abrazos,

PD1: A esto le puedes sumar lo que se compra por parte de las empresas de sus propias acciones, se llama “buybacks”. Es decir, se coge dinero del cash flow, o en muchos casos se pide un préstamo, para recomprar acciones y amortizarlas. Se suele dar cuando no se tiene nada mejor donde invertir, cuando el negocio no se puede expandir más, cuando la mejor opción es quitar acciones propias del mercado. Sus efectos son muy buenos ya que mejoran los ratios, pero si se hace a crédito es una locura…

En esta corrección, la recompra de acciones propias para quitarlas de en medio ha servido para frenar las ventas, pero ¿es repetible? No creo:

El peso de los buybacks es enorme en la liquidez de las compañías:

Es justo lo contrario a lo que han ido haciendo los bancos españoles para pagar el dividendo, vía ampliaciones de capital…: emitían más capital en vez de recortarlo. Pasaron los años y cada vez hay más acciones emitidas. Se contentaron a los accionistas pensando que cobraban un dividendo cada año, pero ahora toca repartir a cada vez más acciones nuevas… Es lo mismo que la evolución de las pensiones en España, que crecen y crecen por culpa de prejubilaciones y más jubilaciones, en un sistema Ponci de engaño total…

Es lo mismo que cuando tiramos de tarjeta de crédito para comprar mierdas. Si lo podemos pagar al cabo de un mes, cojonudo, pero cuando no podemos y lo dejamos a deber de manera sistemática, a un coste de intereses disparatado de más del 20%, que va multiplicando la carga de la deuda con el paso del tiempo, entonces es que nos hemos vuelto locos de remate, como los mismos yanquis:

Es lo mismo que cuando pensamos que ya lo pagaremos y nos seguimos endeudando y endeudando sin freno, pagando intereses por los gastos corrientes y no por los de inversión y dejamos el país con una pelota intratable que estallará en unos años:

PD2: Hay que meter pasión a lo que hacemos cada día. Es la única forma. Nos equivocaremos o no, pero hay que meterle muchas ganas… Averigua lo que más te gusta, y hazlo con pasión, porque esta es la manera con que vas a tener éxito, ya que haciendo lo que más te gusta es la única forma de ser feliz, incluso si no tienes éxito en tus metas…

Y en la vida espiritual pasa lo mismo. Hay que salir de la tibieza, de sabernos cristianos solo la hora de Misa dominguera. Hay que vivir nuestra fe con intensidad y saber trasmitirla a los demás, en las conversaciones, en nuestro actuar…, siendo ejemplares.