Paul Krugman escribe en el New York Times sobre el caso español, y remarca que la política de devaluación interna es muy dolorosa, como bien sabemos aquí. Incide en que se hicieron políticas de ajuste al principio, pero seguimos con un déficit estructural brutal, es decir dejando a muchos años vista el pago de gastos corrientes actuales… ¿Es justo que nuestros hijos tengan que pagar lo que nos hemos gastado estos años en sanidad, en sueldos y salarios de los funcionarios, en chuminadas varias, al monetizarlo en papelitos llamados bonos del estado que se prolongarán en el tiempo? Pues claro que no.

Adjustment in the Euro Area

The crisis in the euro area — as opposed to the broader global financial crisis — began in late 2009. It’s still far from over. But some of the hard-hit peripheral economies, notably Ireland and Spain, are finally growing again. So how should we think about such recoveries, and how do they fit into an overall picture of the single currency’s performance? I thought it might be useful to walk through how I understand the situation, illustrating the argument with data from Spain, which I think of as the quintessential euro-crisis country — a country that didn’t commit any obvious policy sins, but was whipsawed by huge inflows of capital that suddenly reversed. (All data are from the IMF World Economic Outlook database.)

First, a reminder of just how bad it has been, and how far we still are from full recovery:

Notice that at this point Finland — which is suffering from an idiosyncratic shock to its export industries rather than a sudden stop in capital inflows — is doing as badly as much of southern Europe. This is a reminder that the euro system creates huge problems for adjustment everywhere, that this isn’t a one-time problem.

But how would we expect countries to respond to adverse shocks? Contrary to what many people seem to believe, Keynesian-type analysis doesn’t say that countries can never recover without devaluation and/or fiscal stimulus; on the contrary, as I pointed outmore than three years ago, it predicts a gradual recovery through internal devaluation — that is, a depressed economy will cause low or negative inflation, gradually improving competitiveness against other members of the currency union, and rising net exports should drive growth as long as they’re not offset by ever-tighter austerity.

Spanish experience since the euro was created in 1999 does indeed suggest that a depressed economy holds down inflation:

And internal devaluation has slowly improved competitiveness (as measured by relative GDP deflators) against the European core:

What about austerity? Spain did a lot of tightening in the first few years of the euro crisis, but not much since then:

So we would expect, other things equal, to see Spain experiencing faster growth than the rest of the euro area at this point, as internal devaluation improves competitiveness while fiscal policy is no longer tightening the screws.

The question then is, does this constitute any kind of vindication of either the euro or the austerity regime? As you might guess, I’d say that the answer is a clear no. Yes, adjustment can take place even with a single currency; but it’s a very slow and painful process. Yes, growth can resume once you stop imposing ever-harsher austerity; also, if you repeatedly hit yourself on the head with a baseball bat, you will feel better when you stop.

What is true is that the single currency isn’t totally unworkable. It’s just extremely costly.

And on an intellectual level, basic macroeconomics continues to account pretty well for European developments. There’s nothing in recent experience that should shock a Keynesian or cause deep self-doubt.

Abrazos,

PD1: Es problema español es que no tenemos dinero y actuamos muchas veces con esa presunción de que somos ricos…

Esto es lo que somos: Renta per capita:

Hay mucha desigualdad entre los socios de la UE…

Y dentro de España hay mucha desigualdad también… Cuántas veces te he hablado de las dos Españas… Todo sigue igual:

PD2: Infraestructuras: hemos hecho de todo pensando que éramos ricos y ahora hay que pagarlas:

Seguimos dale que te pego al AVE…, siendo conscientes de que no podremos pagar ni el mantenimiento…

¿Volverá a ser la construcción el motor de la economía española? Lo dudo:

PD3: El turismo va muy bien, pero aporta tan poco al total de la economía…, que no nos salva.

PD4: Seguimos con un déficit estructural negativo, es decir, seguimos pasando a deuda pública gastos corrientes (sueldos y salarios, gastos de sanidad y educación…), que se convierten en bonos y se pagarán de forma perpetua (nuestros nietos van a seguir pagando lo que hemos gastado estos años). ¿Cuándo se va a corregir?

PD5: Y como no se reduce el gasto público, se cuadra vía impuestos. Nos tienen fritos…

Y no cuadran las cuentas ni por esas…

PD6: Al final, todos son deudas. Mira la evolución desde 2007 hasta el último dato de 2015:

Mira España, mira Alemania…

Y muchos optan por largarse:

¡Qué pena esa mano de obra cualificada que se larga a buscarse las castañas por ahí, a dar lo mejor de sí a otros!

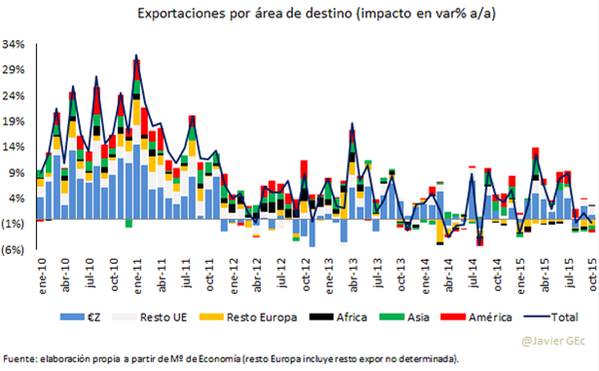

PD7: Y es un camelo que nos salvan las exportaciones. Se vuelven a ir para atrás, y el crecimiento se basa en el consumo, de nuevo. Mismos errores, mismo modelo. ¿Qué pasa si la gente percibe más incertidumbre y gasta menos? Pues para atrás…

PD8: Hay que ser valientes. Hay que tener esperanza y fe, pero hay que ser muy valientes…