Crecimiento económico sin inflación, muchos años de deflación…, y recientes macro paquetes de estímulo financiero para salir del estancamiento… (como me recuerda a lo que nos va a pasar por aquí…)

Pero no parece que lo está consiguiendo, no crece. Japón nos interesa mucho ya que en Europa la sensación es que seguimos sus pasos. De esta nueva recaída económica, la tercera recesión en apenas 6 años, se trata de salir de la misma forma que lo ha intentado Japón y no lo acaba de conseguir. Te lo he contado miles de veces, nos japonizamos…

Y las consecuencias de tanta inyección la tiene el yen y su sector exterior:

Abenomics Keeps Sputtering – What To Do?

We have frequently discussed the nonsensical attempt by Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe and BoJ governor Haruhiko Kuroda to print and spend Japan back to prosperity in these pages. By now it is well known that devaluing the yen has not achieved the desired effect, but rather the opposite. Not only have exports not really received the expected boost, but Japan’s trade and current account surplus have decreased markedly, even posting negative numbers for the first time in decades. Of course, currency debasement never works: it cannot work.

Japan’s current account over the past two decades.

We would like to point out though that a trade or current account surplus is not a measure of a country’s prosperity anyway. So even if the devaluation gambit had “succeeded”, its success would have been meaningless and any positive effects would have been strictly transitory. Japan’s consumers would have suffered just as they are suffering now. As Ludwig von Mises stated with regard to alleged advantages of devaluation:

“The much talked about advantages which devaluation secures in foreign trade and tourism, are entirely due to the fact that the adjustment of domestic prices and wage rates to the state of affairs created by devaluation requires some time. As long as this adjustment process is not yet completed, exporting is encouraged and importing is discouraged. However, this merely means that in this interval the citizens of the devaluating country are getting less for what they are selling abroad and paying more for what they are buying abroad; concomitantly they must restrict their consumption. This effect may appear as a boon in the opinion of those for whom the balance of trade is the yardstick of a nation’s welfare.

In plain language it is to be described in this way: The British citizen must export more British goods in order to buy that quantity of tea which he received before the devaluation for a smaller quantity of exported British goods.”

In short, devaluation means securing a strictly temporary advantage for a small sector of the economy – export-oriented companies – while impoverishing all consumers concurrently. In the end, not even the advantages for exporters will be maintained, as domestic prices will inevitable adjust. As strategies for economic revival go, this has to be one of the most moronic ones ever devised. Not surprisingly, the EU’s coterie of economic planners is also fervently in favor of debasing the euro. Especially France’s government has been quite vocal in this respect, which is telling. The situation in the EU at present is this: the ECB has taken the advice of the biggest economic illiterates in political power in the EU.

Abenomics has lately suffered additional setbacks. It is “succeeding” only in one respect – the yen’s purchasing power has plummeted. GDP has just declined by 7.1% annualized last quarter, reversing the gains of the previous quarter and then some. Both the previous quarter’s reported growth and the subsequent decline have partly been the result of a sales tax hike, so they have to be taken with a grain of salt. It is however conspicuous that virtually every economic datum released since April has come in “worse than expected” – in many cases, much worse.

Japan – annualized quarterly GDP growth rate

As a side effect of the sales tax hike as well as the yen’s depreciation, Japan’s consumer price index has begun to soar. Japanese officials play this down by relying on a “core inflation index” that excludes the effect of the sales tax hike, and consequently argue that the inflation rate is stilltoo low. This obviously matters little to the average Japanese citizen, who has seen his real income melt like a pile of snow in the Sahara. It is unfortunately not possible for Japan’s consumers to pay “seasonally adjusted prices ex the sales tax effect”. Statistical artifice cannot alter economic reality.

Japan’s annual CPI growth rate.

Previously, Japanese consumer prices tended to mildly decline from time to time, thereby enhancing the meager incomes of Japan’s growing class of retirees and the incomes of wage earners. Abe and Kuroda have succeeded in impoverishing them. Mainstream economists all over the world are almost unanimous in their approval of this idiocy.

The Latest Advice

This brings us to the most recent plans and the advice dispensed by assorted bien pensants. Given the recent faltering of Japan’s economy, BoJ governor Kuroda has assured everyone that the central bank stands ready to monetize even more debt. After all, whenever the Keynesian recipe of money printing and deficit spending fails to work, it can only mean that not enough of it has been applied. The fact that it hasn’t worked in 25 years is regarded as clear proof that even more of the same is needed.

Concern has been mounting over whether the economic recovery will continue and inflation will hit the BOJ’s 2% target sometime next year.

“Should conditions emerge where the target becomes difficult to meet, we are ready to make without hesitation adjustments to policy, additional easing or whatever,” Mr. Kuroda told reporters after meeting Mr. Abe over lunch at the prime minister’s office. The consumer-price index, the BOJ’s policy target, has logged year-over-year rises for 14 straight months and stood at 1.3% in July, excluding the sales-tax rise.

Appearing on TV later in the day, the governor refuted views that there was little room for further easing, given the BOJ’s already massive bond purchases. “I don’t believe that there is a limit to additional easing or that there is nothing more we can do.”

[...]

The Japanese economy contracted an annualized 7.1% in the April-June quarter, as consumers tightened their belts and companies slashed new spending following the three-percentage-point rise in the sales tax to 8%.

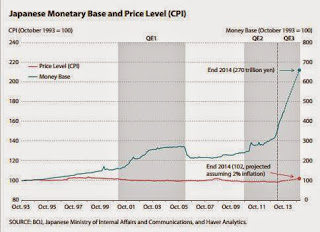

The BoJ’s efforts have blown Japan’s monetary base “off the charts”, but a concomitant reduction in bank credit has meant that very little of this has actually translated into money supply growth – so far, that is.

Japan’s monetary base rockets into the blue yonder.

It must be kept in mind here that this massive rise in the monetary base means that an ever larger share of the fiduciary media in Japan’s banking system have been transformed into covered money substitutes. This makes a deflationary credit collapse less and less likely, and by inference means that the opposite is becoming ever more likely. It cannot be ruled out that faith in the currency one day simply evaporates and that prices will then “catch up” with the monetary inflation that has taken place up to this point.

The main reason why the public’s continued confidence in the currency cannot be taken for granted is the essential Ponzi nature of the BoJ’s debt monetization schemes. By buying ever more government debt with newly issued bank reserves, the government ends up owing more and more of its debt to “itself”. The inherent absurdity of this situation should be obvious.

We can deduce from Mr. Kuroda’s comments that he is not at all concerned that anything untoward could happen. After all, it has all gone swimmingly so far. This unawareness on the part of the BoJ’s planners actually heightens the dangers considerably.

Japan’s narrow money M1 (demand deposits and currency), roughly equivalent to money TMS-1. Note that in spite of the BoJ’s massive ‘QE’ operations, annualized growth has recently declined to 4% from an interim high of 6% achieved in early 2014. All the same, the money supply is up by a factor of six since Japan’s asset bubble burst in 1990. CPI meanwhile has risen somewhat until 1995 and has essentially flat-lined since then – click to enlarge.

So what is the advice dispensed to Japan’s policymakers in the financial press? That’s actually a rhetorical question – they are advised to do what they plan on doing anyway. The Nikkei Asian Review has recently been pondering whether Japan’s economy can “afford” another sales tax hike in 2015. It concludes that in spite of the dangers posed by the government’s debt-berg, only more printing and deficit spending can possibly rescue the economy – and there is of course great urgency:

“Most economists probably feel timid about predicting negative growth at a time when the pros and cons of another consumption tax hike are being discussed. Ryutaro Kono, chief economist at BNP Paribas Securities (Japan), is an exception. He predicts 0.1% negative growth for fiscal 2014.

For many economists who belong to organizations, it seems difficult to make unique and surprising predictions. But importantly, they do not want to see the additional consumption tax hike fall through. If it becomes clear the Japanese economy will post negative growth in fiscal 2014, it will be impossible to discuss another tax increase.

Japan’s fiscal conditions are continuing to deteriorate due to the aging of society. Many economists feel a sense of crisis, fearing that any delay in the additional tax hike would result in the crumbling of confidence in Japan’s fiscal policy.

So, what should be done?

The government and private sector should acknowledge the harsh economic situation and then discuss what measures should be taken. It could be possible to implement a supplementary budget, and embark on additional monetary easing as well as accelerate growth strategies.

The government’s Council on Economic and Fiscal Policy is due to start intensive discussions about the state of the economy on Sept. 16. Unbiased discussions and quick actions are more necessary than ever before.”

To summarize: there is a “sense of crisis” due to the explosion in Japan’s fiscal debt and the danger that confidence in fiscal policy may wane. The best way to counter this is by engaging in more money printing and even more deficit spending (this is what the “implementation of a supplementary budget” means – it means more government spending). This is Keynesian logic and brilliance in all it splendor.

Japan’s total public debt-to-GDP ratio, including an overoptimistic projection – click to enlarge.

Japan’s government deficit as a percentage of GDP.

Conclusion:

We conclude that “more of the same” will remain the agenda until the whole house of cards implodes one day.

¿Hasta cuándo va a seguir estimulando su economía? ¿Qué va a hacer el Banco de Japón con todos esos bonos que anda comprando?

Abrazos,

PD1: Mira las deudas de Japón (en rojo), comparadas con la de los demás bloques:

PD: Y la suma de los estímulos de todos los bancos centrales es insoportable:

¿Hasta cuándo? ¿Qué hacemos luego? Eso no se sabe, les estamos dejando un regalo envenenado a la siguiente generación, o a varias generaciones si me apuras… Abrazos,

PD: Esta viñeta es tragicómica:

¿Estamos así? Más o menos…