Lucha por tener inflación y que no se japonice Europa…, aunque no consigue ninguna.

El dominó diabólico de Mario Draghi

Habrá quien piense que los 385.860 euros que gana Mario Draghi, presidente del BCE, son demasiados. Sin embargo, hay que reconocer que lo complicado de su tarea le está haciendo sudar cada uno de ellos, en opinión de unos para bien y de otros, no tanto.

"The primary objective of the ECB's monetary policy is to maintain price stability. The ECB aims at inflation rates of below, but close to, 2% over the medium term", se destaca en la web del BCE, es decir: el mandato es situar la inflación en el entorno del 2%, cuando ahora es el 0,4% y no se ven expectativas de subidas en el horizonte.

Este mandato tiene su origen en el pavor que generó la hiperinflación alemana de la década de los 20 en el siglo pasado, pero también se basa en un nuevo temor a una deflación (caída sostenida de los precios durante varios trimestres) que paralice las economías y las haga recaer en una recesión duradera. De ahí que el BCE acabe de reiterar que habrá nuevos estímulos en marzo ante una inflación más baja de lo esperado.

¿Esto es bueno o malo?

Si hacemos caso a lo que expertos como @JESUSQ opinan, "un bajo nivel de inflación debido a la disminución de los precios de nuestras importaciones debería ser considerado una magnífica noticia, no luchar contra ello".

Y a la vista está que no es lo mismo tener en cuenta la evolución de los precios en la Eurozonaque figura en la web del BCE:

Que observar la inflación armonizada en la Eurozona (fiebre azul) y mucho menos que mirar a lainflación subyacente, sin energía ni alimentos no elaborados (línea rosa):

Sin embargo, Draghi no solo se enfrenta al problema de si la inflación es demasiado alta (no es el caso) o demasiado baja (parece que sí). También tiene que dar respuesta a otros elementos distorsionadores del mercado que se mueven en un verdadero dominó diabólico.

La ficha de los mercados y la banca

Vivimos un exceso de liquidez sin prececedentes, pero ¿dónde va el dinero? Ya hemos visto que con la enorme volatilidad existente hay quien prefiere incluso pagar a la hora de aparcar su dinero en deuda, por ejemplo española.

Ahora, Draghi amaga con volver a rebajar la tasa de interés de depósito, por la que remunera el dinero que los bancos depositan a un día (como puntas de tesorería), hoy en el -0,30%, para ver si logra que ese dinero se mueva más.

Al mismo tiempo, los tipos reales a largo plazo cercanos a cero unidos a las exigencias de capital derivadas de las nuevas normativas europeas están castigando los márgenes bancarios, lo que explica en buena parte la enorme volatilidad y caídas del sector en Bolsa.

Por si esto fuera poco, los efectos en principio beneficiosos del bajo precio del petróleo (principal causante de la baja inflación) para los países más dependientes, como España, están siendo demoledores para las bolsas y a medio o largo plazo podrían tornarse en negativos también para esos países.

En primer lugar, porque las naciones productoras frenen sus inversiones (recordemos grandes proyectos como el AVE a la Meca) o sus compras en el exterior; además, podría afectar seriamente, ya lo hace, a sus inversiones en deuda de países como España y, en tercer lugar y a más largo plazo, la falta de reinversión en la propia producción de crudo podría desatar una brusca escalada de precios en el futuro.

La ficha de los gobiernos

Francia, por la lucha contra el terrorismo; Grecia y Portugal, con gobiernos de los llamados de progreso; España, con su alta incertidumbre política, solo atenuada a corto plazo por contar con unos Presupuestos aprobados... Por una u otra razón, la relajación en los criterios de déficit se impone en las agendas.

Mario Draghi no se ha cansado de repetir por activa y por pasiva que si los gobiernos no hacen sus tareas de nada servirán las actuaciones del banco central.

La ficha de la guerra de divisas

"A la luz de las experiencia de países europeos y otros que han decidido irse a tasas negativas, vigilamos esa posibilidad, porque queremos estar preparados en el caso de que necesitásemos aumentar la expansión", aseguró recientemente Janet Yellen, presidenta de la Fed estadounidense.

Nadie quiere ceder en lo que se ha convertido en una guerra de divisas soterrada para evitar perder competitividad en una economía enormemente globalizada. Desde hace meses esa ha sido la sensación que China ha dejado en los mercados.

Así pues, mientras Draghi asegura que el BCE hace todo lo necesario (siempre se recordará su famosa frase de julio de 2012) para estimular la economía, el problema es que en el baile del dominó de los mercados, los efectos positivos de sus políticas (y las de los otros bancos centrales) podrían tornarse en negativas. Y peor, cuanto más se prolonguen en el tiempo.

Abrazos,

PD1: En EEUU, la inflación se comporta de forma distinta a Europa: Allí sí que tienen inflación subyacente (la que se calcula sin energía, ni alimentos no elaborados)

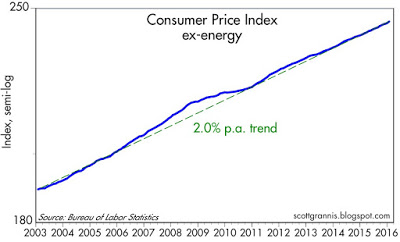

My sense of the consensus on inflation: it's very low, threatens to go negative; central banks seem powerless to boost it, but they need to keep trying because very low inflation is a sign that monetary policy is too tight and threatens widespread corporate bond defaults. The reality, however, is quite different. As I've been pointing out for a long time, if you strip out energy prices you find that the underlying rate of consumer price inflation has been running at a 2% pace for more than a decade. Nothing has changed of late. And there's no reason to think the current rate of inflation is too low.

The chart above says it all. It's the CPI ex-energy index, plotted on a log scale. It's been following a 2% growth rate ever since 2003. Whatever the Fed has been doing or trying to do, they have delivered 2% inflation.

The chart above compares the CPI to the CPI ex-energy. I've highlighted two periods when oil prices suffered a significant decline. I think the current period is playing out almost exactly like 1986. Headline inflation collapsed, but bounced back once oil prices stopped declining.

I note that in the late 1990s inflation was about the same as it is today (about 2%) yet that was a period of very strong growth (about 4% a year for several years). Low and stable inflation is a good thing. The problem today is that oil prices have been incredibly volatile. But as I pointed out the other day, the fundamentals of the oil industry have changed dramatically thanks to new drilling technologies. Governments no longer have the monopolistic control over oil supplies that they used to have. There's a new and important source of supply, and his name is Fracking. Oil prices are not going to decline much more than they already have. Oil demand is on the rise, and new drilling has been shut down dramatically—until prices start to rise again.

Oil prices are likely to be more stable in the future than they have been in the recent past, and that will allow the underlying trend of inflation—2%—to be revealed once again.

As an aside, I should note that the "core" rate of consumer price inflation is up at a 2.3% annualized pace over the past six months. Lower oil prices may be helping other prices to rise, because consumers have more money to spend on other things.

PD2: Los bancos centrales se han quedado sin munición, se han gastado todos los cartuchos para enfrentarse a una crisis que ha demostrado que más liquidez no sirve para que crezcan las economías… ¿Ahora qué? Crecimiento muy flojito sin inflación…, estancamiento.

Según The Economist:

Central bankers are running down their arsenal. But other options exist to stimulate the economy

WORLD stockmarkets are in bear territory. Gold, a haven in times of turmoil, has had its best start to a year in more than three decades. The cost of insurance against bank default has surged. Talk of recession in America is rising, as is the implied probability that the Federal Reserve, which raised rates only in December, will be forced to take them back below zero.

One fear above all stalks the markets: that the rich world’s weapon against economic weakness no longer works. Ever since the crisis of 2007-08, the task of stimulating demand has fallen to central bankers. The apogee of their power came in 2012, when Mario Draghi, boss of the European Central Bank (ECB), said he would do “whatever it takes” to save the euro. Bond markets rallied and the sense of crisis receded.

But only temporarily. Despite central banks’ efforts, recoveries are still weak and inflation is low. Faith in monetary policy is wavering. As often as they inspire confidence, central bankers sow fear. Negative interest rates in Europe and Japan make investors worry about bank earnings, sending share prices lower. Quantitative easing (QE, the printing of money to buy bonds) has led to a build-up of emerging-market debt that is now threatening to unwind. For all the cheap money, the growth in bank credit has been dismal. Pay deals reflect expectations of endlessly low inflation, which favours that very outcome. Investors fret that the world economy is being drawn into another downturn, and that policymakers seeking to keep recession at bay have run out of ammunition.

Bazooka boo-boo

The good news is that more can be done to jolt economies from their low-growth, low-inflation torpor (see Briefing). Plenty of policies are left, and all can pack a punch. The bad news is that central banks will need help from governments. Until now, central bankers have had to do the heavy lifting because politicians have been shamefully reluctant to share the burden. At least some of them have failed to grasp the need to have fiscal and monetary policy operating in concert. Indeed, many governments actively worked against monetary stimulus by embracing austerity.

The time has come for politicians to join the fight alongside central bankers. The most radical policy ideas fuse fiscal and monetary policy. One such option is to finance public spending (or tax cuts) directly by printing money—known as a “helicopter drop”. Unlike QE, a helicopter drop bypasses banks and financial markets, and puts freshly printed cash straight into people’s pockets. The sheer recklessness of this would, in theory, encourage people to spend the windfall, not save it. (A marked change in central banks’ inflation targets would also help: see Free exchange.)

Another set of ideas seek to influence wage- and price-setting by using a government-mandated incomes policy to pull economies from the quicksand. The idea here is to generate across-the-board wage increases, perhaps by using tax incentives, to induce a wage-price spiral of the sort that, in the 1970s, policymakers struggled to escape.

All this involves risks. A world of helicopter drops is anathema to many: monetary financing is prohibited by the treaties underpinning the euro, for example. Incomes policies are even more problematic, as they reduce flexibility and are hard to reverse. But if the rich world ends up stuck in deflation, the time will come to contemplate extreme action, particularly in the most benighted economies, such as Japan’s.

Elsewhere, governments can make use of a less risky tool: fiscal policy. Too many countries with room to borrow more, notably Germany, have held back. Such Swabian frugality is deeply harmful. Borrowing has never been cheaper. Yields on more than $7 trillion of government bonds worldwide are now negative. Bond markets and ratings agencies will look more kindly on the increase in public debt if there are fresh and productive assets on the other side of the balance-sheet. Above all, such assets should involve infrastructure. The case for locking in long-term funding to finance a multi-year programme to rebuild and improve tatty public roads and buildings has never been more powerful.

A fiscal boost would pack more of a punch if it was coupled with structural reforms that work with the grain of the stimulus. European banks’ balance-sheets still need strengthening and, so long as questions swirl about their health, the banks will not lend freely. Write-downs of bad debts are one option, but it might be better to overhaul the rules so that governments can insist that banks either raise capital or have equity forced on them by regulators.

Deregulation is another priority—and no less potent for being familiar. The Council of Economic Advisors says that the share of America’s workforce covered by state-licensing laws has risen to 25%, from 5% in the 1950s. Much of this red tape is unnecessary. Zoning laws are a barrier to new infrastructure. Tax codes remain Byzantine and stuffed with carve-outs that shelter the income of the better-off, who tend to save more.

It’s the politics, stupid

The problem, then, is not that the world has run out of policy options. Politicians have known all along that they can make a difference, but they are weak and too quarrelsome to act. America’s political establishment is riven; Japan’s politicians are too timid to confront lobbies; and the euro area seems institutionally incapable of uniting around new policies.

If politicians fail to act now, while they still have time, a full-blown crisis in markets will force action upon them. Although that would be a poor outcome, it would nevertheless be better than the alternative. The greatest worry is that falling markets and stagnant economies hand political power to the populists who have grown strong on the back of the crisis of 2007-08. Populists have their own solutions to economic hardship, which include protectionist tariffs, windfall taxes, nationalisation and any number of ruinous schemes.

Behind the worry that central banks can no longer exert control is an even deeper fear. It is that liberal, centrist politicians are not up to the job.

PD3: He leído en el evangelio que debemos amar a nuestros enemigos, aunque nos hagan el mal. ¿Quiénes son mis enemigos? ¿Los separatistas catalanes, el coletas y sus secuaces, Rajoy, Pedro Sanchez, Ribera? No sé si lo son, pero hay tanta enemistad de muchos contra ellos que me impresiona. La gente está asustada de lo que se nos viene encima y se aterra de los dirigentes que tenemos, odian a varios de los que te he nombrado… ¿No habría que amarlos? Cuando rezo el Rosario, al final se reza una Padrenuestro por los gobernantes y su buen hacer. ¡Qué buena costumbre! Debemos rezar por ellos para que se iluminen y hagan cosas eficaces para el bien común y, sobre todo, no podemos odiarlos, sino todo lo contrario, debemos amarles y perdonarles, incluso si hacen el mal, hasta a “el coletas”…