Tenemos hasta el REY aprobando el nuevo paquete de recortes en el Consejo de Ministros del viernes. Ayer te di las pistas de lo que se rumorea. Algo más tibio parece que viene. Insuficiente a mi entender. Te apuestas a que dura unas horitas el rebote sólo… Ya verás. No le meten mano a las duplicidades de las CCAA, ni ajustan el tamaño del Estado a la nueva realidad recaudatoria actual y futura…

La Burbuja de la Administración Pública

En cualquier negociación es recomendable situarse en el lugar del otro para intentar prever cual será su razonamiento durante la misma. España se encuentra en plenas conversaciones con nuestros socios europeos sobre la profundidad del ajuste necesario de nuestras cuentas públicas y el calendario de aplicación del mismo. Basta analizar los datos de la evolución de los ingresos, gastos y número de empleados públicos durante los últimos diez años para constatar que existe una burbuja en la Administración Pública española. Es la primera conclusión a la que habrán llegado nuestros socios.

Durante el periodo de crecimiento económico 2002-2007, los ingresos públicos no dejaron de aumentar, inducidos en parte por el boom inmobiliario, generando una burbuja de ingresos para las Administraciones Públicas. Las AA.PP. no tardaron en incrementar sus gastos y en considerar el incremento de los ingresos extraordinarios de momentos de boom económico e inmobiliario como ingresos estructurales.

A medida que aumentaban los ingresos, la Administración Pública fue aumentando su nivel de gasto y el número de trabajadores del sector público. El estallido de la burbuja inmobiliaria y la llegada de la crisis económica nacional e internacional han reducido los ingresos de forma significativa, mientras la inercia de crecimiento de los gastos se prolongó incluso durante 2008 y 2009, años de plena crisis económica. Entre 2002 y 2007, los ingresos públicos se incrementaron un 53%. En el mismo periodo, los gastos aumentaron en menor proporción, un 45%. Pero la perversa inercia de aumento de los gastos públicos, y la inelasticidad a la baja del gasto, provocó que aun cuando los ingresos públicos cayeran significativamente en los siguientes años, el gasto público siguió incrementándose año atrás año hasta alcanzar su nivel máximo en 2009. Así, pese a que los ingresos públicos se incrementaron en 86 mil millones de euros entre 2002 y 2009, el aumento del gasto público fue de 200 mil millones de euros en el mismo periodo.

La medida del déficit público se realiza siempre utilizando el ratio Déficit/PIB, que compara el exceso del gasto público sobre los ingresos (déficit) con el Producto Interior Bruto (PIB) del país en cuestión. Para lograr una percepción más clara del exceso de gasto, entendible por cualquier ciudadano, sería conveniente comparar los gastos públicos con los ingresos públicos. Midiéndolo de esta forma, el déficit de las cuentas públicas respecto a los ingresos en los últimos tres años es escalofriante. En 2009, 2010 y 2011 las AA.PP, gastaron respectivamente un 31%,25% y 24% más de lo que ingresaron.

La Administración Pública ha sufrido una burbuja de ingresos asociada al boom inmobiliario y a los años de fuerte crecimiento económico. Por mucho que se pretendan subir los impuestos, será imposible alcanzar los niveles de ingresos públicos del año 2007 en los ejercicios venideros. A modo de ejemplo, los ingresos de impuestos vinculados a las transacciones inmobiliarias, como el ITP (Impuesto de Transacciones Patrimoniales), han reducido su recaudación un 65% desde el pico de 2007 hasta el fin de 2011. La recaudación por Impuesto sobre Sociedades en 2011 apenas ha sido un tercio de la lograda en 2006. Exprimir a los ciudadanos y a las empresas a base de más impuestos para intentar mantener una Administración Pública sobredimensionada sólo conseguirá demorar la llegada del crecimiento económico y empeorará la situación.

Observando el gráfico anterior, parece meridianamente claro que el nivel de gasto actual de la Administración Pública es insostenible y fruto de un nivel de ingresos públicos que sólo era un espejismo.

La creencia de que los ingresos públicos de la época de euforia eran estructurales y no coyunturales, ha llevado a las AA.PP. a incrementar sus gastos fijos y, por supuesto, el número de trabajadores de las AA.PP. (no sólo funcionarios). El número de trabajadores del sector público se incrementó en 321.000 personas entre 2002 y 2007, hasta alcanzar los 2.913.000 empleados.

Desgraciadamente, la negación de la crisis económica, que en 2007 ya era evidente, y la irresponsabilidad de algunos dirigentes políticos, ha provocado que pese a la reducción de los ingresos públicos, el número de trabajadores del sector público haya seguido aumentando en 217.000 personas en los cuatro últimos años. Las CC.AA. son las grandes "generadoras" de este empleo público, habiendo creado 247.000 puestos de trabajo públicos adicionales.

España se ha comprometido a reducir su déficit público al 3% del PIB en 2013 y al 1% en 2015. Es muy factible que consiga un alargamiento de los plazos pero este ajuste no se podrá llevar a cabo sin una "poda" sustancial de los gastos de las AA.PP., que conlleva necesariamente una reducción del número de trabajadores públicos, que de forma aberrante ha seguido incrementándose incluso una vez iniciada la crisis económica. Esto es lo que piensan nuestros socios europeos y, ciertamente, es difícil no estar de acuerdo con ellos.

Mientras tanto, la tela se nos larga de España, la de los guiris y la de los listillos hispanos… Esperate a que conozcamos los datos de mayo y junio… Ay, ay, ay…

¿Qué va a hacer Alemania con tanta pasta que le entra? Tendrá problemas. Imagínate que te entre en el país tanta pasta…, qué gozada. Pero, tendrá problemas… Es demasiada pasta para uno sólo. Tendrá problemas...

We have covered the topic of the German TARGET2 imbalances previously, both from the perspective of what catalysts can lead the Bundesbank to suffering massive losses (the one most widely agreed upon being a collapse of the Eurozone, which explains why even discussions of that contingency are prohibited in Europe), from the perspective of its being an indirect current account deficit funding mechanism, and from the perspective of what is the maximum size TARGET2 imbalances, funded primarily by the Bundesbank, can grow to before eventually causing irreperable damage to the Bundesbank. Still, there appears to be ongoing mass confusion about the topic, with numerous economists proposing contradictory theories, all of which supposedly rely on traditional economic models. Today, to provide some additional and much needed color, we once again revisit the topic of TARGET2, and this time we look at arguably the most critical question: what happens when the TARGET2 imbalance bubble ultimately pops. And here is where the true cost to Germans becomes apparent, because there is no such thing as a "borrowing from the future" free lunch. Which is precisely what TARGET2 does, only instead of a direct cost, the post-TARGET2 world will result in the now traditional indirect cost of all monetary experiments gone awry: runaway inflation.

As Goldman summarizes:

Who ultimately pays for TARGET2 losses? Higher inflation part of the bill

...

[T]he important point in the context of the financial risk for Germany from the growing TARGET2 imbalances is that, in the event of a break-up of the Euro area, the price paid would not necessarily be in the form of a massive recapitalisation of the Bundesbank, which could endanger the solvency of the German government itself. Rather, it would come in the form of higher inflation, as Germany faced the financial costs of the Bundesbank's rising net claims vis-à- vis the other Euro area central banks.

In other words, if Goldman sought to appease Germans' fears about the aftermath of providing what effectively equates to "costless" bailouts, in the form current account deficit funding for the PIIGS, by telling them the final cost may well be a tide of runaway inflation, one which may come far sooner than most expect, we are skeptical they have succeeded.

Full report from Goldman:

Assessing the financial risks of TARGET 2 for Germany

As Germany recorded current account surpluses from the early 2000s, its financial exposure to the rest of the world rose. While Germany's net international investment position (NIIP) was close to zero at the turn of the century, it had risen sharply to close to €1trn by 2011. This significant rise in German net foreign asset ownership also necessarily implied an accumulation of the financial risks associated with these assets. However, both the ownership and composition of these net claims against the rest of the world have changed significantly over time: banks and other financial institutions have reduced their net holdings of foreign assets substantially since the start of the crisis in 2007, while there has been a sharp increase in the public sector's foreign exposure.

The rise in the net foreign asset position of the public sector has taken place through two channels:

- The financial help provided to the Euro area periphery through the EFSF and—in the case of the first Greek programme—other government-owned institutions has led to a direct increase in financial exposure for the German government.

- The other, and more relevant channel in terms of the volumes involved, has been the Bundesbank's TARGET2 claims against the Eurosystem.

It is thereby no coincidence that the increase in net foreign assets on the Bundesbank's balance sheet roughly matches the decline seen on banks' balance sheets. Thus, the TARGET2 imbalances, at least so far, have mainly replaced financial risk that was previously sitting on private-sector balance sheets.

Further movement of capital from the periphery to Germany—for example, as peripheral households transfer deposits to Germany—would imply additional, genuinely new external financial risk for Germany, reflected in a further rise in TARGET2 claims.

But it is important to bear in mind when assessing Germany's external financial risk that, as a central bank, the Bundesbank's ability to deal with financial losses incurred as a result of these exposures is of a different character to the ability of the private sector or government. In particular, the operational capacity of the Bundesbank would not necessarily be significantly impaired even if it were forced to run temporarily with significant negative equity.

A current account surplus implies more foreign assets

Throughout the 1980s, Germany recorded a rising current account surplus (see Chart 1). This surplus quickly turned into a deficit as the reunification boom led to a sharp increase in imports. It took until 2001 before this current account deficit was turned back into a surplus. The combination of weak domestic demand, a recovery in competitiveness and strong external demand then pushed the current account surplus to a record high of around 7.5% of GDP in 2007.

As a consequence of the growing current account surpluses recorded over the past ten years, Germany net international investment position (the difference between all foreign assets owned by the German private and government sector and German assets owned by foreigners) has increased sharply (see Chart 2). At the end of 2011 Germany's NIIP stood at close to €1trn.

The assets that make up Germany's NIIP include bonds (whether issued by governments or corporates), loans, stocks and foreign direct investment. But regardless of the specific characteristic of the underlying asset, they all also represent a financial risk to some degree, in the sense that the return on these assets is not certain—and could even be zero.

Changes in sectoral risk exposure to the periphery

The aggregate figures for the NIIP blur the significant differences that exist at the sectoral level. Chart 3 shows the NIIP broken down into different sectors, such as Monetary Financial Institutions (MFIs) (which are mostly commercial banks), non-financial corporates and private households, the government and the Bundesbank.

The chart illustrates three noteworthy points:

- Banks/MFIs have reduced their NIIP sharply. German banks' NIIP rose from a negative -€300bn in the middle of 2000 to +€520bn by the end of 2008. Since then, their NIIP has declined to €170bn at the end of last year. Meanwhile, German banks' gross credit claims against the periphery have declined from almost €600bn to around €300bn (Chart 4).

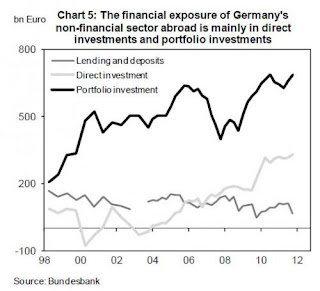

- Corporates and private households have seen their NIIP increase further during the crisis. Companies and private households represent the bulk of Germany's NIIP. Roughly 60% of these assets (€700bn) are portfolio investments, 30% are direct investments, and 10% are lending and deposits held at foreign banks (Chart 5).

- Foreigners hold a significant share of Germany's public debt. The German government sector (all levels, excluding Bundesbank) was indebted on a net basis vis-à-vis the rest of the world by more than €1trn at the end of last year.

Exposure to the periphery

Looking at Germany's country-specific exposure, German net investment in peripheral economies stood at around €1trn at the beginning of 2012, the bulk of which is concentrated in Italy, Spain and Ireland (Chart 6 shows the net investment of all sectors vis-à-vis the countries in the periphery). Note, however, that these figures do not reflect the net claims of the Bundesbank vis-à-vis the Eurosystem due to TARGET2 imbalances. As a claim on the ECB rather than a specific country, these claims are not against a specific country and are therefore recordedas net investment into the Euro area.

Most German investment in the peripheral countries reflects ownership of companies or production facilities located there. Roughly a third of the net investment in the periphery is lending (Chart 7). Lastly, we take a look at bank lending to peripheral countries (Chart 4). While Germany's overall financial exposure to the periphery has been broadly stable, banks have reduced it significantly since the beginning of the crisis.

Pulling all these data together, we can see a clear shift in the composition of Germany's net foreign asset position: financial institutions have sharply reduced their exposure to the periphery , while the public sector has increased its claims significantly. The main channel through which this transfer of risk has taken place has been the TARGET2 system.

TARGET2 imbalances are on the rise

Commercial banks use the so-called TARGET2 system to facilitate money transfers across the Euro area. One crucial feature of TARGET2 is that claims between national central banks resulting from cross-border money flows between commercial banks are not settled. If, for example, a commercial bank in Greece wants to transfer money to a German bank, the Bank of Greece simply asks the Bundesbank to credit the account of the German commercial bank with that amount and at the same time debit the account of the Bank of Greece with the same amount. As a central bank, there is no funding required for the Bundesbank in this operation. The Bundesbank simply 'prints' the money it credits to the account of the German commercial bank.

Before the crisis, flows between the periphery and Germany were broadly balanced. Banks and nonfinancial corporates borrowed from German banks and companies in order to finance, in large part, the trade deficit the periphery held with Germany. This implied that money flowed from the periphery to Germany (to pay the bill for imports) and from Germany to the periphery (to provide a credit such that the bill could be paid). But as German banks reduced their lending to the periphery on account of concerns about counterparty risk (Chart 4), capital flows have become a one-way street. Consequently, the net claims of the Bundesbank against the Eurosystem have risen sharply (Chart 8).

What are the financial risks from TARGET2?

In assessing the financial risk stemming from the increase in the net claims of the Bundesbank against the Eurosystem—the TARGET2 imbalances—it is important to bear in mind that, at least so far, they mostly replace debt held by German banks. Put differently, the financial risk for the country as a whole has not changed significantly on the back of the rising net claims of the Bundesbank.

This may no longer be the case, however, once rising net claims reflect not only normal commercial and investment activities, but rather deposit flight from the periphery to Germany. So far, there is no real evidence that private households or companies are shifting their deposits to Germany in a significant way. But a genuine deposit flight from the periphery to Germany would lead to a significant increase in the Bundesbank's net claims.

After all, peripheral private households alone hold more than €1.5trn of deposits. To be sure, the Bundesbank's rising net claims vis-à-vis the Eurosystem would only represent a financial risk if a country were to leave the Euro area. Moreover, the losses of the Eurosystem are shared among all remaining countries. Thus, the financial risk for Germany has actually been reduced, as potential private losses have been replaced by losses that will be shared by the Eurosystem. However, in the event of a break-up of the Euro area, the losses from the Bundesbank's net claims would materialise on the Bundesbank's balance sheet alone.

Bundesbank operational effectiveness not endangered by potential losses

At this point, it is not possible to calculate the exact size of the Bundesbank's potential losses in the event of a complete break-up of the Euro area. First, the amount would depend on how much further net claims rise. Second, it is not clear how much of these claims would need to be written down. Arguably, other national central banks/governments would have little incentive, or the economic means, to honour any of these liabilities. But depending on the circumstances of the break-up some mutual agreement about a haircut could be found.

That said, even though we do not know ex ante the size of the losses the Bundesbank faces, we can say that, in principle, these losses would not impair its ability to operate monetary policy. Put differently, it is not the case that the Bundesbank would first need to be recapitalised before it could once again conduct monetary policy at the national level. Indeed, there are several examples of central banks that have operated with negative equity and have been able to maintain price stability. The Bundesbank could, for example, simply insert a claim against the German government on the asset side of its balance sheet in order to maintain its balance sheet in balance in an accounting sense.

Who ultimately pays for TARGET2 losses? Higher inflation part of the bill

This does not mean that potential TARGET2 losses would not imply a significant challenge to the Bundesbank. Its first challenge would be to stabilise inflation expectations. Expectations about future price developments play a crucial role in the inflation process: if economic agents were to expect, for whatever reason, an increase in prices and adjust their economic decisions accordingly, expectations would become self-fulfilling. This is why central banks in general monitor inflation expectations carefully.

How would inflation expectations react if the Bundesbank were to incur significant losses and had to operate with negative equity? Again, there is no easy answer to this but, according to the so-called fiscal theory of the price level, the credibility of a central bank also depends on its solvency. The Bundesbank's solvency would be questioned if the losses exceeded the net present value of its future income (seignorage). A backof-the-envelope calculation of this net present value suggests the Bundesbank has economic capital of around €2trn. Thus, the Bundesbank has significant capacity to absorb losses before endangering its ability to guarantee price stability.

There is also a more mechanical way of assessing the potential inflation risk stemming from Bundesbank losses on the back of the TARGET2 imbalances. These imbalances are the result of rising deposits on the balance sheets of German commercial banks. These deposits ultimately represent a claim on German GDP, as the holders of the deposits could spend the money sitting in their accounts. Another way to look at this is that rising deposits at German banks imply that monetary aggregates are rising in relation to the underlying German economy.

Whether these deposits would be inflationary or not would depend on several factors—not least how quickly these deposits are spent. But it is clear that the greater the amount of deposits held by non-residents after the breakup, the greater the potential inflationary risk. A high degree of uncertainty surrounds all of this and it is not possible to be more precise about the potential inflationary implications. But the important point in the context of the financial risk for Germany from the growing TARGET2 imbalances is that, in the event of a break-up of the Euro area, the price paid would not necessarily be in the form of a massive recapitalisation of the Bundesbank, which could endanger the solvency of the German government itself. Rather, it would come in the form of higher inflation, as Germany faced the financial costs of the Bundesbank's rising net claims vis-à-vis the other Euro area central banks.

Pues eso, estamos todos los países muy entrelazados. Así que si se larga la pasta a un país de manera dominante, tendrán problemas al que le sale el dinero y al que le entra… Ni lo dudes. A esperar el GRAN MUSTIO, que está cada vez más cerca… Un abrazo,

PD1: ¿Cómo nos afecta la crisis? Mira lo que contestan:

Hay gente que no tiene pasta ni para estudiar, ni para emprender, ni para tener niños ni casarse… De vuelta al hogar paterno… Ay, qué lata van a dar a los pobres padres que se las presumían felices de haberse liberado de la carga de los hijos… Es el terror de verte sin dinero y sin futuro. Es el terror de saberte metido en medio de una crisis sin el hábito anterior de cobrar por trabajar… Terrorífico.

PD2: Finlandia no quiere que cobremos nada del rescate, no se fía de que vayamos a pagar de vuelta… Olé por nuestros socios…

Finland would rather exit euro than pay for others: Jutta Urpilainen, Finance minister

HELSINKI: Finland would consider leaving the eurozone rather than paying the debts of other countries in the currency bloc, Finnish Finance Minister Jutta Urpilainen said in a newspaper interview on Friday.

"Finland is committed to being a member of the eurozone, and we think that the euro is useful for Finland," Urpilainen told financial daily Kauppalehti, adding though that "Finland will not hang itself to the euro at any cost and we are prepared for all scenarios."

The finance minister stressed that Finland, one of only a few EU countries to still enjoy a triple-A credit rating, would not agree to an integration model in which countries were collectively responsible for member states' debts and risks.

She also insisted that a proposed banking union would not work if it were based on joint liability.

"Collective responsibility for other countries' debt, economics and risks; this is not what we should be prepared for," Urpilainen said.

Urpilainen acknowledged in an interview with the Helsingin Sanomat daily that Finland "represents a tough line" when it comes to the eurozone bailouts.

"We are constructive and want to solve the crisis, but not on any terms," she said.

As part of its tough stance, Finland has said that it will begin negotiations with Spain next week in order to obtain collateral in exchange for taking part in a bailout for ailing Spanish banks.

Finland has also voiced concern about an agreement reached at an EU summit in Brussels last week to use the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) to buy bonds to ease the unbearable borrowing costs which are squeezing Spain and other vulnerable eurozone economies.

And last year, Finland created a significant stumbling block for the eurozone's second rescue package for Greece, agreeing to take part only after striking a collateral deal with Athens in October 2011

PD3: If debt continues to rise and money printing comes back stronger, bonds will be a terrible place to be. Jim Rogers

PD4: El desempleo femenino más bajo en Europa es en Tirol (Austria): 2.7%. El más alto en Ceuta (España): 39.1% En el conjunto de parados de toda Europa, 8 de 10 regiones que están peor son españolas…:

PD5: La estulticia española: futbol a todas horas: EGM de España: Marca: 2.978.000 de lectores de media al día. 20Minutos: 1.986.000. El País: 1.899.000. As: 1.490.000. El Mundo: 1.219.000. La Vanguardia: 816.000. ABC 641.000. La Voz de Galicia: 640.000… Pronto es la revista semanal con mayor audiencia (3,5 millones de lectores), seguida por Hola (2,3 millones). Muy Interesante, por su parte, encabeza el ranking de las revistas mensuales con 2,17 millones de lectores. National Geographic (1,3 millones) y Saber Vivir (1,18 millones) ocupan el segundo y tercer lugar, respectivamente. Así nos luce el pelo. Y para lo que cuentan los periodistas… y las mierdecillas de revistas…

PD6: Alemania se financia a 5 años al 0,34%. El bono español a 5 años cotiza al 6,04%... Las comparaciones son odiosas… y a 10 años, peor. Qué sí, que hay alguien que gana con la crisis. Han dejado de exportar a los PIGS; nos han sustituido por emergentes y su financiación es de coña. ¿No estarán deseando que esto dure muchos más años de lo que nadie quiere? No seas mal pensado Juanito…, que ganan ellos y perdemos nosotros, por habernos pasado y haberla liado parda. Verás la que nos damos… Bueno, no lo verás, la estás viendo ahora mismo…

PD7: ¡Dos Coca-colas 12 Euros! ¿El secreto de sobrevivir a la crisis? Subir los precios.

PD8 Ya te aviso, yo no invertiría hoy ni en Apple, ni en Google, ni en Amazon. Mira la comparación con el SP&500. Hay otras cosas mejores que no han hecho esto todavía…, pero que lo harán en los siguientes años.

PD9: Cada persona se convierte de una forma distinta. Mira que ejemplo de conversión más bonito…

"Encontré la fe católica gracias a la búsqueda de la belleza"

El escultor japonés Etsuro Sotoo explicó a los jóvenes asistentes al Encuentro Internacional de Estudiantes Universitarios (UNIV) en Roma, cómo encontró a Dios a través de la belleza y la arquitectura.

Etsuro en la conferencia del Univ

Según informó la agencia Gaudium Press, el artista, encargado de los diseños y construcción del Templo Expiatorio de la Sagrada Familia en Barcelona, quiso profundizar en el pensamiento del Siervo de Dios Antoni Gaudí para poder ejecutar su obra. Entonces conoció el verdadero sentido de su trabajo y la verdadera belleza. "Mi nombre es Etsuro, que significa 'hombre feliz', y se ha cumplido: la verdadera felicidad es la de ahora, al encontrar la fe", afirmó con orgullo.

En la conferencia titulada "Tras las huellas de Gaudí", Sotoo compartió con los estudiantes el camino de su conversión: "Al principio, estudiaba mucho las palabras de Gaudí, las maquetas de Gaudí, pero llegó un momento en que tenía que realizar un proyecto que ni siquiera Gaudí había imaginado ni proyectado". El artista japonés decidió tratar de comprender la perspectiva del arquitecto español. "Intenté mirar a dónde miraba Gaudí. Para eso tengo que estar donde estaba Gaudí, y ¿dónde estaba Gaudí? Gaudí estaba en el mundo de la fe. Por lo tanto, para mí era natural que quisiera entrar en ese mundo de la fe, para conocer más, o para poder realizar el trabajo encargado".

El descubrimiento de la fe católica, partiendo del pensamiento del Siervo de Dios, colmó plenamente todas las expectativas del artista: "Desde ese momento cambió totalmente mi vida. Entendí todas las palabras; aunque no perfectamente, como el agua clara que yo deseaba", afirmó Sotoo.

La conversión también llevó al escultor a comprender la profundidad espiritual que Antoni Gaudí veía en la vocación artística. El artista japonés reflexionó sobre una conocida frase del Siervo de Dios: "El arte es el resplandor de la luz de la Verdad: sin Verdad no hay arte". Las conclusiones de esa reflexión cambiaron la forma de entender su actividad. "Soy simplemente un picapedrero, pero busco el arte", afirmó Sotoo. "Encontrar la verdad es muy difícil, no siempre se consigue. Por lo tanto, mi pensamiento es que no existe el oficio de artista. Solamente quien busca el arte, el arte como resplandor de la luz de la verdad, ésta quizá es la persona más cercana al artista".

El Siervo de Dios y reconocido arquitecto catalán Antoni Gaudí, dedicó los once últimos años de su vida a la construcción del Templo Expiatorio de la Sagrada Familia, que llamaba cariñosamente "la Catedral de los Pobres". Vivía con notable sencillez y austeridad, al punto de ser trágicamente confundido con un mendigo en el accidente de tránsito que le causó la muerte.

El Siervo de Dios asistía diariamente a la Eucaristía y llevaba una constante vida de piedad. Varias de sus obras, entre ellas el ábside de La Sagrada Familia, fueron declaradas Patrimonio de la Humanidad por parte de la UNESCO.